Art History 101

These 3 Recreations of Velásquez Prove He’s an Important Figure in Art History

Though perhaps not widely known outside of those with a particular penchant for art history and museum-going, the Spanish painter Diego Velásquez’s legacy has been championed by 20th century artists moved by his style. Picasso, Dalí, and Bacon are amongst the artists who’ve paid tribute to Velásquez with works that either directly recreate or emulate his work. In fact, Dalí’s trademark mustache was inspired by Velásquez – who too was mustachioed.

Velásquez was court painter of King Phillip IV from the early to mid 17th century, producing many fancy Baroque (think exuberant backdrops and fabrics with moody lighting) portraits of Spain’s ruling class, children on horses, other notable figures (poets! court fools!), and commoners. His style mixed elements of Dutch portraiture with Italian sharpness and his late portraits included loose brushwork that would be referenced by the impressionists. Read below for a quick look at three tributes: Dalí’s Velasquez Painting the Infanta Marguerita, Picasso’s Las Meninas, and Bacon’s Pope Innocent X.

Dalí’s Velásquez Painting the Infanta Margarita with the Lights and Shadows of His Own Glory (1958)

Velásquez’s 1680 masterpiece Infanta Margarita Teresa in a Blue Dress is the subject of Dalí’s interpretation, building out Velásquez’s original into a dreamlike web of surrealist motifs. In Dalí’s hypnagogic painting—which looks quite nearly like both a stained glass window and a photo negative—the artist married his love of Velásquez with his enthusiasm of metaphysics and Abstract Expressionism.

Dalí’s increasing interest in quantum mysticism, blooming later in his life, was expressed in his surreal explorations of consciousness and how we perceive reality (recall his melting clocks). Dalí’s layered Infanta composition includes a meta reference to Velásquez painting, The Prado and its windows, and a large, specter-like Teresa. The style of the work is thought to be an ode to Abstract Expressionism in its use of space throughout the canvas and symbolic gestural etchings.

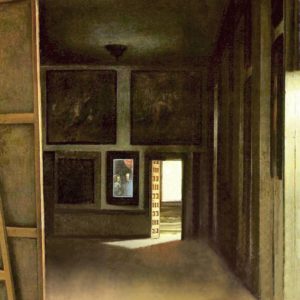

Picasso’s Las Meninas (1957)

Considered to be his magnum opus, Velásquez’s Las Meninas was a pioneering take on perception and illusion that explores the relationship between subject, viewer, and artist. The original, created in 1656, depicts little Margaret Teresa surrounded by Spanish court members and beside Velásquez and his canvas; on the mirror in the back of the room is a selfie style reflection of the king and queen. The composition was unconventional for the time and its many characters and quirks have led to myriad interpretations, which would take too long to run through but are worth reading about if painting theory is your proverbial cup of tea.

Beloved 20th century Cubist Picasso (did he love painting theory?) undertook an extensive series of 58 reinterpretations of Las Meninas. He didn’t alter the scene or characters but painted them in his style, cube-y, and repainted the scene as a way to study how subtle changes in form and rhythm can alter the overall scene. On this practice, Picasso is quoted, “I would say..what if you put them a little more to the right or left? I’ll try to do it my way, forgetting about Velázquez” (source).

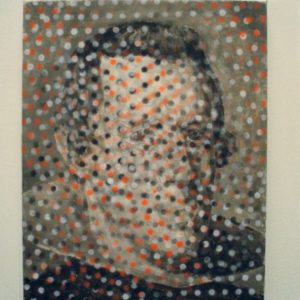

Bacon’s Study After Velásquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1953)

Francis Bacon, too, embarked on an endless quest—50 paintings, many he destroyed—to create and recreate Velásquez’s 1650 portrait of the contentious Pope Innocent X. The original was noted for Velásquez’s bold treatment of the pontiff’s expression, a realist depiction of Innocent X’s shrewd disposition. He also, frankly, looks old, a quality the pope is said to have recognized and grudgingly respected.

Following this unflinching approach, Bacon lent his penchant for the dark and disturbing to his numerous Pope tributes. The most famous is a 1953 version that presents a downright ghoulish Pope, silently screaming, an angry apparition-like figure simultaneously materializing from and dissolving into gestural, abstract expression-y drapes. Bacon built on the subtle emotion of the original, adding layers which epitomized the postwar artistic atmosphere of disillusionment and anguish. It’s a crazy painting for a crazy time.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections, and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.