Inside the Studio

Gregg Chadwick

Gregg Chadwick

Favorite material to work with?

I have always been entranced by oil paint and often prepare colors from dry pigments and linseed oil. A few years ago while in Bruges, I marveled at the skin tones in the almost 600 year old paintings by the Flemish masters. This alchemy between material and subject seems to have prompted the 20th century modernist Willem de Kooning to declare, “Flesh was the reason that oil paint was invented.”

What themes do you pursue?

For me as a painter, the fleeting movement of time is compelling. Often, inspiration is fueled by the ethereal experience of time as it is lived “in a moment.” I am captivated by the human experience of “noticing”, struggling to deeply see, to really grasp the hard-to-describe stuff that happens to us in the phenomenon of a moment. Sometimes it is what is heard or seen or felt in a flash of time. Sometimes it is what comes from a quick look or a brief connection of some sort, a pause in a flow of time passing. Other times it is the seemingly long lasting moment that pulls me in…a mesmerizing gaze, or a lingering mood. I express this inspiration through color and light. The figures in my paintings express what it means to be alive in the mixing and crossing of the 21st century, in the U.S. and across the globe.

One other value or theme that I hold dear is diversity. Even in art there is inequity. Walk through most art museums and the majority of the human subjects are white and wealthy. I feel a need to remedy this in my own work and reflect everyone around me.

How many years as an artist?

When I am at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, I always visit the painting I first remember: Rembrandt’s iconic group portrait The Sampling Officials of the Amsterdam Drapers Guild. As a six year old during a family reunion in Europe after my father returned from the Vietnam War, I stood before the painting and recognized it as the same image on the Dutch Masters’ cigar box, my father’s go-to brand. The connection was phenomenal; I was hooked and I knew that someday I would become an artist.

Where is your studio?

I create my artwork in an old airplane hangar in Santa Monica, California. The recurring sound of airplane take-offs and landings from the active airport runaway outside my studio continually reminds me of my own history of travel.

What was the best advice given to you as an artist?

“Paint your worlds.” -RB Kitaj at UCLA’s Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

Just months before his death, I saw the painter RB Kitaj after a UCLA sponsored presentation he gave at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Kitaj saw a card gripped in my hand of my painting, A Walk with Ganesh, and he started our brief conversation saying, “Is that for me? I would like to have that.” I handed him the card and watched him examine the image of the painting in his hands, and then my face as we talked. Moved by our discussion, I went home and painted Kitaj as he appeared that evening; white beard, roaring voice, stern focus, like a prophet calling figurative artists, in particular, to “paint your worlds.”

Art school or self-taught?

I took art classes at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington DC when I was in High School. Studying in Washington DC engendered in me a great interest in art and social justice as evidenced in the Smithsonian, the National Archives which houses The Bill of Rights, the Lincoln Memorial, and now the Holocaust Museum. Carrying these lessons forward, I went on to earn a Bachelor’s Degree at UCLA and a Master’s Degree at NYU, both in Fine Art.

Prefer to work with music or in silence?

Each group of artworks that I create seems to have its own soundtrack. Since I work on many paintings at once, I often use particular songs or musical tracks as a key to unlock a previous creative state. Currently I am working on a series of paintings under the group title – The City Dreams. David Bowie’s new song Where Are We Now? seems to be the musical key to this body of work. Where Are We Now? is as much a painting in soft greys as it is a song. A quiet rhythm of drums and synth warp and weft with minor key piano chords and Bowie’s plaintive, elegiac voice. Set in a Berlin of memory and dream, Bowie’s voice and lyrics question the themes of human bondage, release, freedom, doubt, ageing, and death. I, too, aspire to create visual remarks upon these themes.

What is/was around the corner from your place?

From my studio at the Santa Monica Airport, literally off Ocean Park Boulevard, I often walk out the door and see the evening light filtered through my memories of Richard Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park series and a chance meeting I had with Diebenkorn when I still lived in San Francisco. One morning on a walk from my Market Street loft, with a book by Robert Hughes in hand, I spotted Richard Diebenkorn leaning up against a BART entrance watching the cable car turnaround across Market Street. Diebenkorn was captivated by the movement of the conductors as they spun the car around on a giant wooden turntable. I stopped, leaned up against a wall, and flipped through Robert Hughes’ Nothing If Not Critical until I reached his essay on Diebenkorn. I read slowly, pausing often to gaze up at Diebenkorn as he gazed at the forms moving across Powell Street. Eventually, I closed the book, walked over and thanked Richard Diebenkorn for his art and inspiration. He smiled and tears seemed to well up in his eyes, as he said, ‘Thank you. I am glad that my work inspires you. Is your studio nearby?’ I nodded and tried to say something about ‘the interplay between figuration and abstraction in his work.’ Diebenkorn was frail at this point and seemed to know that he didn’t have much longer to live. I didn’t want to take him away from his moment alone in the morning light on Market Street. I thanked him again and moved on. Richard Diebenkorn died soon after in 1993.

What do you collect?

I collect Japanese ukiyo-e prints. I have a small collection, particularly emphasizing the woodcuts of Ando Hiroshige.

Favorite contemporary artist?

The Japanese-American contemporary artist Masami Teraoka is a masterful painter. Across his fruitful career, Masami Teraoka has used depictions of the figure to grapple with the pain and poke fun at the foibles of our human existence. Masami looks back to the art of the past, at times ukiyo-e prints and other times to Renaissance Italy, to find clues to help unravel the mysteries of art and life.

Who are your favorite writers?

I have a voracious appetite for books and often collaborate with writers on projects and workshops. The art writer Peter Clothier has been a huge inspiration to me as well as the San Francisco author Phil Cousineau who continually surprises me with his words and ideas. The novelists I find indispensible include David Mitchell, Salman Rushdie, Sherman Alexie, Haruki Murakami, and Don DeLillo. Poetry is a continual source of inspiration to me including the work of Philip Levine, Carolyn Forché, and WS Merwin. Books by Jared Diamond, Pico Iyer and Lawrence Weschler also hold a prized place on my shelves.

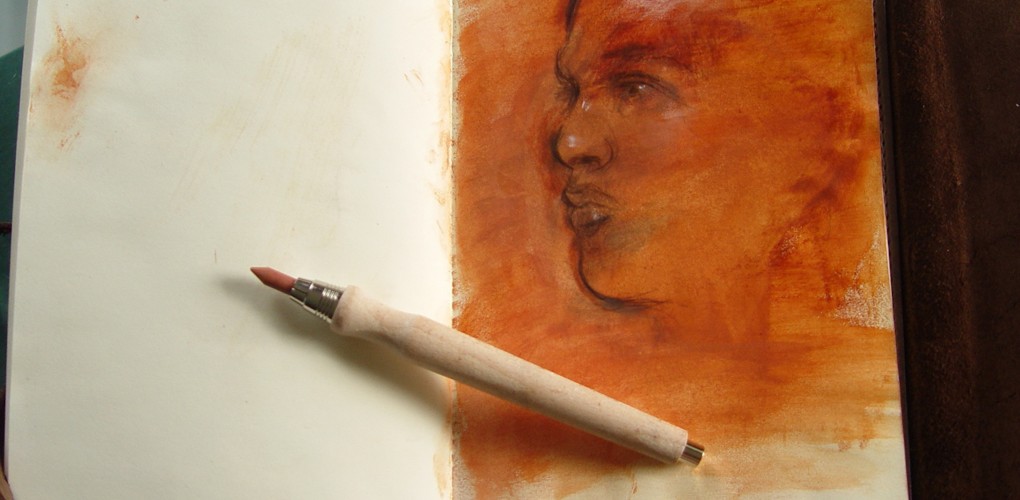

Use anything other than paint?

I also create monotypes. A monotype is generally made by brushing printer’s ink onto a smooth surface such as a glass or metal plate. The image is then transferred to paper before it dries, using a printing press or other means of pressure. I usually use a copper plate on which I paint an idea in oil based etching inks. Next I lay the plate onto the bed of a printing press and put a sheet of blank paper on top of the ink-laden plate. The plate and paper are then run through the printing press under great pressure.

Because most of the image is transferred in the printing process, only one strong impression can be taken, hence the term monotype (one print). Additional impressions of the residual image are often printed (ghosts). They are significantly fainter than the first pull, yet at times these lighter, open images are successful as works of art.

The personal nature of the monotype suited experimental artists from William Blake to Edgar Degas to Milton Avery to Mitchell Friedman. These artists used the monotype process to fashion works of great depth and mystery. Their artworks inspire my own.

Is painting dead?

No, painting is not dead but painting continually needs to be reengaged and rethought. Like Walter Benjamin, I am interested in the potency of a work of art. Benjamin wrote, “That which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art.” I too am convinced that a powerfully composed, vibrant painting creates its own presence, its own aura. By engaging with an artwork’s idiosyncrasies and roughhewn edges, the individuality of a handcrafted work of art can help us appreciate the individuality of humans as well. Painted images are both immediate and beyond time. They can cut through the visual white noise that surrounds us. Paintings can speak where words are not enough.

Favorite brush?

My collection of brushes spans my entire life. I started painting as a kid and rarely throw a brush away. I take particular care in the cleaning and preservation of these tools and use the brush washing experience as a form of meditation. For me, taking time to hear the swish of brushes in cleansing water is akin to listening to the breath in more formal meditation. During these moments my mind is stilled.

Final Thought

As a painting nears completion I remain aware of the Japanese aesthetic concept of wabi-sabi: nothing lasts, nothing is finished, and nothing is perfect.