Inside the Studio

Juliet Vles

Juliet Vles

What are the major themes you pursue in your work?

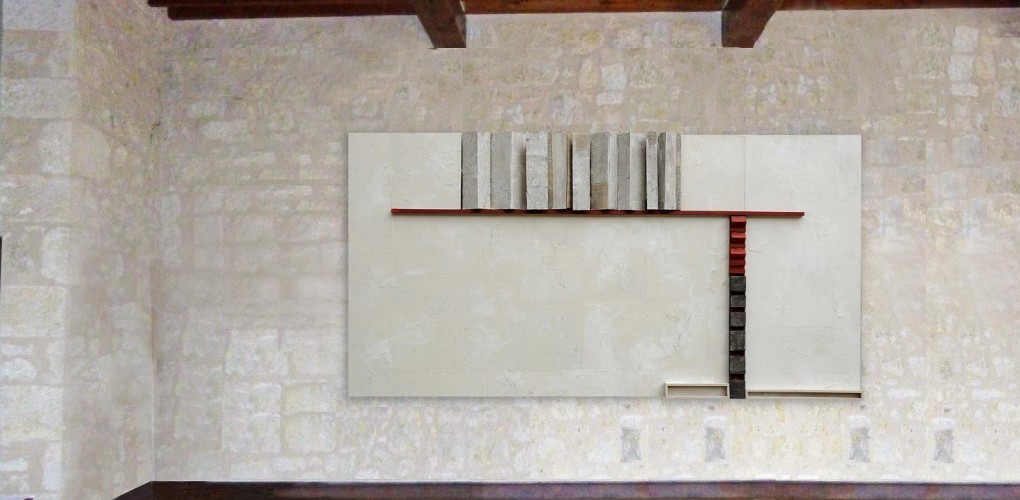

In my work, as in my life, I am guided by two seemingly contrasting priorities, which in reality are two sides of the same coin. With my abstract work I try to contribute, in my own modest way, to the beauty, harmony, and general goodness of our existence. With Bruce Chatwin, I believe that art, especially abstract art, has a hidden subversive power that can very effectively undermine totalitarian tendencies simply by imposing its own vision of truth and beauty. Conforming to the arte povera doctrine, and the material used – industrial paint, glue, paper, plywood – has no intrinsic monetary value. The legitimation of the oeuvre is purely artistic. For my assemblage work, I also use found objects which are inserted «brut» so as to avoid all risk of prettifying the work. In my recent work, I increasingly abandon the notion of making images and rather see my wall sculptures as an extension of architecture. In a way, I am building (strictly non-religious) sanctuaries within an often threatening environment.

The object of my satirical work, complementary to abstract expression, is to denounce the pitfalls of the above mentioned environment (in my case the western capitalist-cum-human-rights formula), whose attractive façade hides some very dark niches indeed. The recent brainscapes-series around the “Illustrated Man” raises what might well turn out to be the most pressing question of our century: knowing how thoroughly we are predefined by our genetic code and education, do we still believe in free thought and self-determination, or are we just a lot of robots ‘programmed to believe that man is born free?’

What was the best advice given to you as an artist?

Bruce Chatwin: “Authoritarian societies love images because they reinforce the chain of command at all levels of hierarchy. But an abstract art of pure form and colour, if it is serious and not merely decorative, mocks the pretensions of secular power because it transcends the limits of this world and attempts to penetrate a hidden world of universal law.”

And by the same author: “Never let anything artistic get into your way.”

Prefer to work with music or in silence?

In silence. The importance of silence in my abstract artwork is so fundamental that without it, most of my oeuvre simply would not exist. I suppose, and hope, that my work is impregnated by the stillness and concentration on the essentials which are the parameters of my creation – and that this feeling communicates itself to the spectator.

Curators often tell me that visitors who first enter my exhibitions tend to stand still for a moment and take a deep breath before even starting to look at the individual pictures. If this means that I have succeeded in creating little spots of breathing space for both myself and others, then I’ll die happy.

If you could only have one piece of art in your life, what would it be?

I cannot even start to imagine a world with only one artwork in it. But if you force me to choose, it would be Chillida’s Wind Comb. Of course the sea, the sky and the wind that are part of this incredibly beautiful work should be part of the package…

Who are your favorite writers?

I have been immersed in literature since early childhood and have been a ferocious reader for sixty years now. In order to answer this question thoroughly, I would need to write some twenty pages at least – which might be found a bit long in this context. So here is a very random choosing of some of my favorites: Dostoyevsky’s Idiot; Kazantzakis’ Christ Recrucified; Doris Lessing’s Shikasta, for giving us the only more or less probable theory about the origins of mankind (even if the author is wise enough to stress that she is writing fiction, not anthropology). I also love Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus for its exuberant fantasy and baroque language; Leonora Carrington’s Hearing Trumpet for its rebellious geriatric spirit; Dieter Zimmer’s Tiefenschwindel for cleansing the world of Freudian charlatanry; Plutarch’s biographies for their analytical intelligence and human spirit. And, last but not least, Stanislav Lem’s Solaris for its profound understanding of the hazards of extraracial communication and, by the same author, Imaginary Magnitude and A Perfect Vacuum.

The book I most enjoyed reading recently was Simon Winchester’s The Professor and the Madman, which is about the making of the Oxford English Dictionary (not a subject that would normally excite me…), and the book I am most looking forward to reading in the near future is Michael Schmidt-Salomon’s Hoffnung Mensch.