One to Watch

Jazoo Yang Makes Art That Refuses To Forget

Jazoo Yang Makes Art That Refuses To Forget

Jazoo Yang began making art not by painting in a studio but by exploring construction sites, where she encountered enclaves of family homes as they were being demolished to make way for new real estate development. Struck by the doggedness of residents who stayed until the end—and baffled by the speed of her native South Korea’s dramatically changing cityscapes—Jazoo created the first instantiation of her iconic Dots project in Busan, wherein she covered the exterior walls of houses set for demolition with her own thumbprints. Thumbprints are a type of signature used for legal documents in South Korea, and in this repetitive, durational project, they acted as a binding pledge to remember the lives led in these homes.

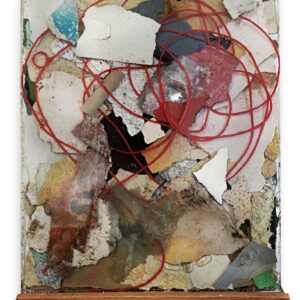

This promise to remember guides Jazoo’s work. Recently, Jazoo has expanded her Immanence and Materials series, in which she takes found objects from city streets and demolition sites and casts them in resin. Against the lightning speed of gentrification and the capitalist imperatives to accumulate, discard, and forget, Jazoo suspends her found materials in time, allowing them to assert their own presence and insist on their own remembrance. Elevated to the status of painting (the evocative term Jazoo uses to describe her artworks), Jazoo’s discarded objects become beautiful in their suspension and speak for the past lives in which they were embedded, as well as the countless other discarded items buried in landfills, willed to be forgotten.

Though many of Jazoo’s works stand alone, they also include site-specific works, such as The Brick, Youngdo (pictured above). A work in progress, The Brick, Youngdo consists of cast resin shaped from the bricks of a since-demolished building in Youngdo. Ultimately, Jazoo’s resin bricks will be inserted into a new building set to be constructed on the site of the old one.

Jazoo began her practice in her home country of South Korea, but her universally resonant approach has seen her complete site-specific projects in Stavanger, Norway, and St. Petersberg, Russia in recent years. In her current home base of Berlin, a city long marked by the spectral remnants of war and the Berlin Wall, Jazoo continues her daily practice of salvaging fragments from the city streets.

Tell us about who you are and what you do. What’s your background?

I’m a painter from Korea and currently live and work in Berlin. I started my art practice when I was almost [in my] 30s. When I decided to become an artist — after working as a designer in a video game company in Seoul — I spent my weekends breaking into construction sites and painting on the walls of the to-be torn-down buildings. It was not really graffiti per se. The walls were canvas to me.

During these trespasses, I found that there were still residents remaining in their homes, actually living right at the construction site. They refused to move, nor did they have the money to. A combination of reasons led me to the encounter between me in the transitory space and the people who have their life and living memory planted in that solace.

What does your work aim to say? What are the major themes you pursue?

I use a variety of media, such as painting, sculpture, installation, performance, video work, and street work, and recently I am also trying to work on media art. But I also call myself a painter. All of my work is an attempt [at the] expansion of the realm of painting.

Can you walk us through your process for creating a work from beginning to end?

I have long formed this daily routine to start my day by going around my apartment and neighborhood. And I collect materials. Some of them form part of the Immanence series (Materials series). I work in a variety of ways in my studio, but to focus on the Immanence series and explain the work process:

First, pour the resin into the mold and put the collected materials into the resin. Resin is a liquid with strong fluidity like water, so materials float on the resin. As time passes and the resin hardens, the materials also find their place. Repeat this process to create multiple layers.

Also, since the resulting surface is the bottom part of a mold, I cannot predict the result while working. This causes tension, like gambling every moment. However, the gambling for creating coincidence combined with intuition and an unconscious motive goes beyond my intention.

Do you remember the first artwork you made from found materials? What was that process like?

There was an old house in Busan, South Korea, originally built in a Japanese style in the 1930s. It was a private residence until [the] 1990s, after which it had been abandoned for over 30 years until it was demolished in 2016 as part of a redevelopment business around Choryang-dong, Busan. I was offered a project for the house before it completely disappeared. At first, I envisioned a mural, but I didn’t want to cover up the memories of that old house with paint. So I started collecting debris from the home, which led to the Materials [and Immanence] series, where I showed collected objects and materials during the project.

Who are your biggest influences and why?

I think I am affected by everything, including all the people I meet, the environment I belong to, and all the music and art I see and hear. In particular, I get a lot of help and inspiration from my partner, who is also a musician and an artist.

How does your work comment on current social and political issues?

When I lived in Seoul, which is changing at a speed that cannot be physically followed, I became interested in the city itself and the artificial materials that make up [the city].

After the pandemic, I’m expanding my interest in nature, which coexists with us in the city.

Any political or social issue affects an individual like me much more directly than I thought. I think there is only individual difference in whether or not [someone reacts] sensitively to it. I try to feel and react to them as sensitively as possible. And I express those feelings that cannot be expressed in language through my work.

If you couldn’t be an artist, what would you do?

It was my dream to be an archaeologist like Indiana Jones.

Prefer to work with music or in silence?

Of course, music!

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections, and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.