Art News

Frida Kahlo: On Animal & Mesoamerican Symbology

The elusive Frida Kahlo was known for her captivating artworks, her volatile yet impassioned marriage to Diego Rivera, her hard fought battle with her deteriorating health, and her eclectic lifestyle that came along with the motley company she kept. Born to an Oaxacan mother and a German father, she grew up in a free-spirited yet strongly political environment and began taking art lessons at a very young age. During her childhood, she had contracted polio which left one of her legs thinner than the other. Shortly after her recovery, she had been involved in a nearly fatal car accident which had a lasting impact on her overall health and wellbeing. Because of her poor physical condition, Kahlo was never able to mother her own children. Feeling lonely and depressed, Kahlo filled her home (known as ‘Casa Azul’ located in the Coyocán neighborhood of Mexico City) with a menagerie of animals that included spider monkeys, cats, birds, and indigenous hairless dogs called Xoloitzcuintli. Recognizing her pets as soulful and insightful creatures, she frequently portrayed them ― notably her monkeys Fulang Chang and Caimito de Guayabal, and her deer Granizo ― throughout her oeuvre.

Infatuated with their Mesoamerican roots, both Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera collected important artifacts from these early civilizations. This had extended to Kahlo’s collection of pets, many of which were representative of Aztec and Mayan cultures. Monkeys, for example, were highly revered by the Aztecs as deities of fertility. In a way, it can be said that Kahlo’s fluid sexuality (Kahlo was known to be a philanderer, having had multiple affairs with both men and women) resonated with that of her pet monkeys due to their rambunctious and unapologetically sexual nature, which might also explain why she had depicted them as her equals. The extremely intelligent Xoloitzcuintli dogs she kept were also very important for the Aztecs, as they were representative of the underworld. If not eaten for special sacrificial ceremonies, the dogs were buried along with their owners to safeguard their souls after death.

These animals played both a significant role in her life as they did in a number of her works, helping her to effectively tell her stories.

In Self Portrait with Monkeys (1943), Frida portrays herself as an almost divine figure, gazing nonchalantly at the viewer and flanked by four spider monkeys ― one of which tugs at her left breast in a childlike manner. The monkey on her right rests upon her arm, pointing at a detail of her shirt which strongly resembles the Aztec Ollin, an emblem of the day-name found in the Tōnalpōhualli calendar. Ollin, which is recognized for earthquakes and disruption, is represented by Xolotl, a dog-like deity who (unsurprisingly) is the ancestral breed of the exact hairless dogs Kahlo kept as pets. A guide to the underworld, Xolotl was often rendered as deformed and symbolized sickness and death. Given the circumstances that Kahlo was herself deformed from her sickness and accidents, the Ollin on her shirt carries a lot of symbolic weight.

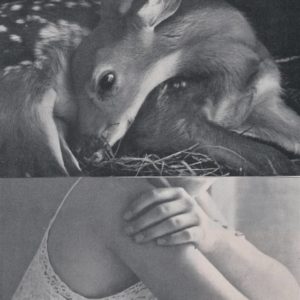

Frida Kahlo was born on the ninth day of the Aztec calendar, which was closely aligned with the underworld. Therefore it was thought that she believed her suffering and pain was her destiny. In The Wounded Deer (1946), a self-portrait depicting Kahlo’s face on the body of her pet deer Granizo, the number nine appears twice ― nine trees line the background and nine arrows pierce her chest and side. This, along with the symbolic portrayal of her as a deer with its raised right foot (Frida’s right foot was affected the most by polio), as well as the laying branch in the foreground, all point to Mexican folklore concerning fatality and misfortune.

Self-Portrait With Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940) portrays Kahlo in the center foreground again, this time flanked by a monkey and a black cat. Thought to be a reference to Christ’s sacrifice, she wears a thorn necklace from which a dead hummingbird is suspended like a pendant. The Aztec people worshipped Huītzilōpōchtli, the god of sacrifice and war portrayed by a hummingbird, which again points to the long-fought battle Frida faced with her pain and suffering. In Mexico hummingbirds also represent luck, however, a dead one may imply that Frida’s good fortune has run out, especially considering the circumstances. Other symbolic elements such as the butterflies and the cat, all point to Kahlo’s fatality.

Through meaningful symbology tied to animals and her Mexican heritage, Frida Kahlo has been enchanting viewers with her unique storytelling. To this day, we remember Kahlo as an influential figure in the art world who continues to inspire millions of artists around the world.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections, and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.