Art History 101

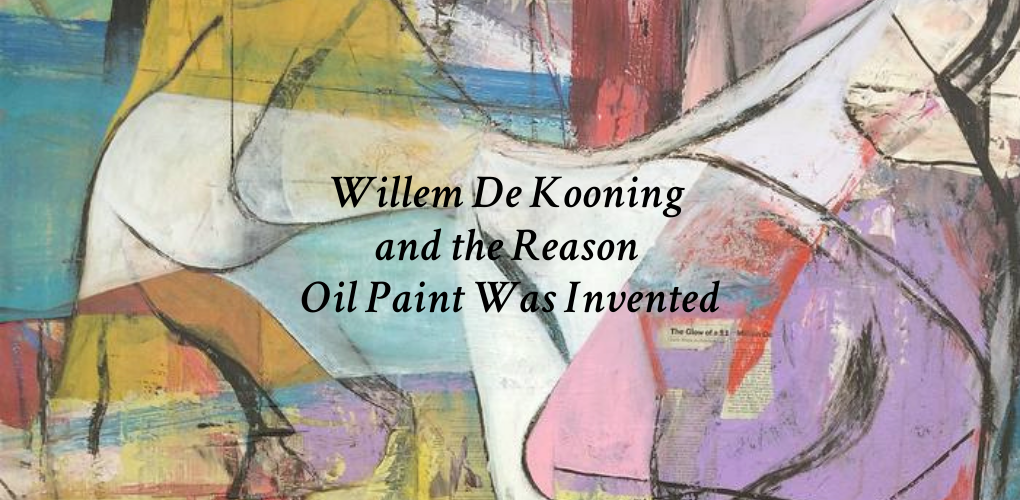

Willem De Kooning and the Reason Oil Paint Was Invented

Perhaps Abstract Expressionism’s most radical departure from the norm was its denial of representation. The painters who came to be known as the New York School forsook any sign of narrative, figuration, or representation of the exterior world in their paintings, opting instead for what they considered a pure exploration of paint’s sensual and emotive potential. So it’s somewhat antithetical that one of the movement’s most revered painters, Willem de Kooning, enthralled critics and fellow artists with his human figures and landscapes—the very subjects a competitive and at times dogmatic art world thought to be irreconcilable with artistic progress.

While for many, Jackson Pollock may be the first Abstract Expressionist to come to mind, Willem de Kooning, with his idiosyncratic blend of representation and abstraction, is widely considered the “artist’s artist” of the movement. His analytical contemplation of cubism, expressionism, and surrealism and his masterful handling of paint resulted in slick, sensuous works that were above all a celebration of paint’s movement and tactility. Like his fellow abstract expressionists, de Kooning was formally interested in pushing the boundaries of paint as a medium—however, he also waxed that “flesh is the reason oil paint was invented,” and therefore the human body was perhaps the best vehicle for exploring the medium’s potential.

Willem de Kooning’s rise to art world fame took a delightfully meandering path. De Kooning was born on April 24, 1904, to working class parents in Rotterdam, Netherlands. Taking an interest in art and design at an early age, he apprenticed with a design firm at the age of 12. After training in fine art at Rotterdam Academy (which, in 1998, was renamed after him in his honor) a 22-year-old Willem stowed away on a ship bound for Argentina. When the ship docked in Virginia, de Kooning slipped past immigration, bound, illegally, for New Jersey, where he began supporting himself as a house painter. From there, he headed to New York, where he would work as a commercial designer and befriend the likes of Arshile Gorky and Stuart Davis, immersing himself in an avant garde art scene just on the cusp of supplanting Paris as the capital of modern art.

In the midst of the Great Depression, de Kooning was commissioned to design public murals as part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) program. Though de Kooning left the WPA after just two years over fear of exposing his immigration status, the experience encouraged him to pursue painting full-time, and the large scale of the mural designs—and the broad brushes handy to him as a house painter—no doubt influenced the scale and gesture of his paintings.

It wasn’t until 1948, at the age of 44, that Willem de Kooning would have his first solo show. Held at Charles Egan Gallery in Manhattan, de Kooning exhibited a series of gestural, large-scale black-and-white paintings, as well as dense, oleaginous abstracts. With the shadow of Paris looming over the competitive New York School, de Kooning worked strategically with Cubism in mind, even noting that “Picasso is the man to beat.” With his Charles Egan show, de Kooning posed a painterly response to Cubist structure, using organic curves and fluid brushstrokes just on the verge of muddiness to carve out the fragmented figures and intersecting planes characteristic of Cubism.

In contrast to the inward trend of Abstract Expressionism, de Kooning recognized the exterior world’s impact on art making, once proclaiming, “Even abstract shapes must have a likeness.” In his abstract compositions of the late 1940s and 50s, hints of figures emerge but recede into chaotic pictorial space before they are fully articulated. De Kooning’s fractured figures come to bear in his aptly titled 1950 painting “Excavation,” wherein teeth, eyes, jawbones, even birds and fish emerge from the fray.

De Kooning brought figures even closer to the fore with his infamous Woman paintings, a series of primitivist figures with jutting limbs and stark facial features which he’d often labor over for years, obsessively adding and scraping away paint. De Kooning even let the impurities of pop culture seep into the purportedly autonomous act of painting—in his circa 1952 “Woman on cardboard,” for instance, he cut out a woman’s mouth from a cigarette ad and pasted it onto his figure. Unabashed in his commitment to the purportedly outmoded human figure, de Kooning also challenged the prevailing modernist theory of painting as an autonomous act, a bold disposition that would give way to the forces of Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol. With his aggressive brushstrokes and brazen choice of subject matter, de Kooning perhaps anticipated the iconoclastic milieu that would follow Abstract Expressionism—as Peter Schjendahl once wrote of the artist’s freneticism, “The very ruin of the world seems to drive his brush.”

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections, and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.