Art History 101

Why Is Duchamp a Divisive Figure?

As most art enthusiasts or museum goers know, art has the power to elicit different effects in people. By definition, art stimulates an emotional response. But what is art, even?

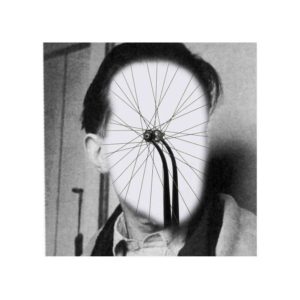

Understanding what art is or what it looks like is an ever-changing landscape. The milieu of the twentieth century birthed a series of art movements that challenged what art meant and what it looked like. Synonymous with the avant-garde, Marcel Duchamp was considered a revolutionary of his time. Throughout his seminal career, both his ideas and artworks rejected conventional practices of art making, and questioned notions of the authorship in art and the sanctity of the art object. During his lifetime, he was the most enticing member of the avant-garde; members of the Cubists, Futurists, Dadaists, and Surrealists both, at times, rejected him and wanted to claim Duchamp as their own.

Looking back at his career, above all, Duchamp was a pioneer of conceptual art, an art movement that’s known to baffle or even inspire onlookers to ask, “Is this art?” In celebration of Duchamp’s 130th birthday on July 28th, let’s take a look at how three of his artworks caused controversy at the time, but would pave the way for conceptual artists and redefine how we think about art.

Nude Descending the Staircase, No. 2

Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 is considered to be both the marked end of Duchamp’s painting career and his first (of many) works that provoke significant controversy by artists and onlookers alike. The painting depicts a figure walking down a staircase in combined motions, similar to Eadweard Muybridge’s photographs of moving figures. With the stylistic leanings of cubism in its use of contoured figure and geometric fragmentation, the work’s effect of dynamic movement also brought in elements of Futurism.

The stark geometric nature of the artwork redefined the nude, much to the chagrin of French Cubists, whom claimed, “A nude never descends the stairs–a nude reclines.” Duchamp’s sharp-edged figures shook up the art history canon, saturated with nudes depicting classical soft beauty.

Fountain

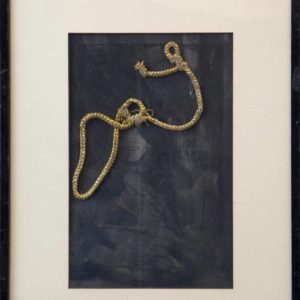

Duchamp was a harsh critic of what qualified as art, and his found object “Readymades” sought to remove both the hand of the artist and the notions of sanctity of the art object. The most famous of his Readymades and an icon of 20th century art, Fountain, repurposed a men’s urinal and added simply “R. Mutt 1917” to the side. In response, the Society of Independent Artists—a society of which Duchamp was a member and therefore entitled to blanket acceptance of all work—rejected the work and hid it from view, prompting Duchamp and one other member to quit.

One can understand why the work was controversial. Aside from being literally a toilet, Duchamp purchased it from a sanitary ware supplier, adding an additional layer of being a mass-produced, machine-manufactured object. The committee claimed its exclusion was due to its scatological nature, which could not absolutely be considered an artwork, but the work surpassed its nature in questioning the medium and inspiring others to follow suit.

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, or “The Large Glass”

One his major works during his lifetime was The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, often called The Large Glass, which Duchamp worked on from 1915 to 1923. Duchamp first conceived of the artwork in 1913, making multiple sketches, notes, and even preliminary sculptures for the final artwork. The finished product stands at over nine feet tall and utilizes materials such as glass, foil, varnish, wire, and dust. Notes Duchamp made during the process of creating The Large Glass were meant to be included with the sculpture during exhibition, breaking the forth wall between creator and artwork and exposing the concepts and thoughts driving the work.

Although enigmatic like many of his previous works, The Large Glass contradicts Duchamp’s previous inclinations to remove the hand of the artist. These notes, referred to as The Green Box, describe Duchamp’s new iconography for sexual desire and frustration. The bride is depicted on the upper panel of glass, and the bachelors are arranged in a circular formation in the lower panel. Due to being in different panes/planes, the bachelors cannot fully communicate with the bride or show their devotion, invoking sexual tension. The Green Box notes both illuminate and complicate meaning garnered from the piece.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections, and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.