Art History 101

The Beginnings of British Romanticism

In honor of John Constable’s birthday month (it was his 241st birthday June 11th), let’s celebrate by talking about Constable’s prominent perch in the landscape of art history as one of the leading lights of British Romanticism – and how his work evolved from two giants of eighteenth-century British art, Joseph Wright of Derby and Thomas Gainsborough. Plus, some tricks for how to distinguish the three painters on your next trip to a museum. If you want to further hone your ability to identify and appreciate the subtleties among works by famous artists, check out the Name That Painter blog, or follow along on Instagram.

Joseph Wright of Derby

Let’s get started with Joseph Wright of Derby, a Neoclassical painter who was an important forerunner to the Romantic movement. Wright is probably best known for his dramatic candlelit scenes celebrating the Enlightenment, including this one:

An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768) by Joseph Wright of Derby. (Image: The National Gallery – London, UK)

His cinematic use of tenebrism, a very pronounced chiaroscuro, marked by jarring contrasts of light and dark, with darkness almost consuming the frame, recalls the paintings of French Baroque painter Georges de La Tour:

The Penitent Magdalene (c. 1640) by Georges de la Tour. (Image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art – New York, NY)

Unlike Georges de la Tour’s paintings, in which a candle represents the religious – a votive offering to God – Wright’s light source represents the scientific.

There’s an undeniable dynamism to Wright’s genre scenes. Compare them to the stiffer portraits by neoclassical giant Jacques Louis-David, painted at the height of his powers. David was a Neoclassical painter through and through, a rigid disciple of order, harmony and rationality. His paintings are symmetrical, austere, and cerebral.

Wright seems to have hopped from the Neoclassical to the proto-Romantic with relative ease, painting many of his first landscapes based on his travels to Italy, including the beautiful moonlit scene of the Bay of Naples, “Vesuvius from Posillipo by Moonlight (1774).” (Image: Private collection)

If Wright is best known for his paintings of Enlightenment scientists – and I am not exaggerating when I say that An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump especially belongs on any list of the best paintings in the history of Western art – they may not be his most important.

Why? Well, his Enlightenment scenes owed much to Caravaggio in lighting and composition. What was radical and new was the way he applied tenebrism to landscapes. Unlike his genre scenes that had one foot in the Neoclassical and one foot in the Baroque of the Caravaggisti (followers of Caravaggio), Wright’s landscapes prefigured an entire movement, Romanticism, which opposed the order and balance of the Enlightenment.

Even though landscape painting was, at this time, a much less popular and prestigious form of painting, Wright seems to have been drawn to it again and again. His travels to Italy must have inspired him to stop painting genre scenes of Man on the cusp of conquering Mother Nature in the midst of the Enlightenment. Vesuvius has almost the opposite viewpoint: Man dwarfed by an active Vesuvius, threatening to engulf the seaside resort town any second.

Upon his return from Italy, Wright settled in Bath for almost two years, returning to portraiture without much success. He relocated to Derby, where he painted this Neoclassical potboiler:

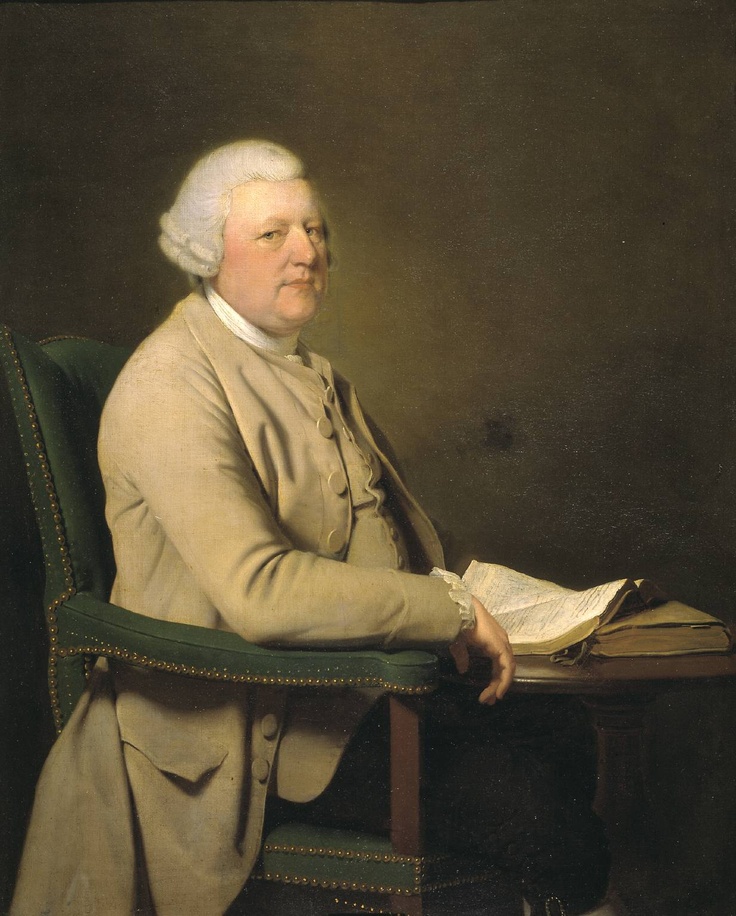

Richard Cheslyn (1777) by Joseph Wright of Derby. (Image: The Tate Britain – London, UK)

It’s a perfectly good Neoclassical painting of one Richard Cheslyn, esquire, pretending to be reading a book and hoping he’ll impress his friends. And for all its technical mastery, it is very much been-there-done-that. Now compare it to a similar composition by Wright:

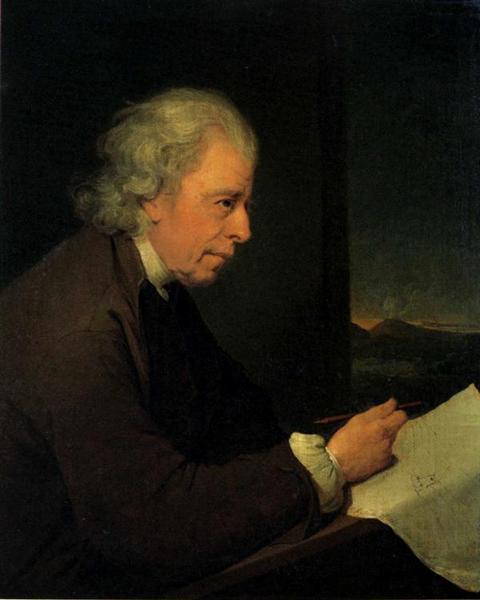

“John Whitehurst” (c. 1782-1783) (Image: Private Collection)

This painting is a perfect blend of Wright’s oeuvre up to this point in his career. It’s of John Whitehurst, a well-regarded Derbyshire geologist and hydraulic/pneumatic inventor. This isn’t just a society portrait. This dude is hard at work, thinking about how to tame Mother Nature, when a puffing, doom-and-gloom volcano sits right outside his window! As far as I know, there are no active volcanoes in Derbyshire. Or anywhere in the UK. Wright is injecting a Romantic capriccio (architectural fantasy/dreamscape) painting into a Neoclassical portrait of an Enlightenment thinker. And the pose really sells the painting. Unlike Cheslyn, Whitehurst is not “posing” for his painter. He is “alone,” burning the midnight oil, lost in thought.

Joseph Wright of Derby was a seriously versatile artist. If you want to pick him out, look for his early genre paintings of industrial workers, scientists, and pseudo-scientists gathered around a single, dramatic artificial light source in a crowded room otherwise cloaked in darkness, like in An Iron Forge (1772), or his mid-career landscapes of Italian bays, volcanoes and caverns lit by the moon, as well as English countrysides lit by the moon.

Dovedale by Moonlight (1784) by Joseph Wright of Derby. (Image: Wikipedia)

Maybe next time you’re at your local museum, you’ll not only be able to pick out a Wright painting; you’ll be able to pick out when he painted it!

Now let’s talk about painter behind door number two, Thomas Gainsborough.

Thomas Gainsborough

Like Joseph Wright of Derby, Thomas Gainsborough painted portraits out of financial necessity but preferred landscapes.

Gainsborough basically copied Dutch Baroque master Anthony van Dyck’s compositions for his portraits of rich people (so many decorative rocks, randomly placed draperies, and giant pots!). Well, he borrowed from the Dutch for landscapes too, specifically from Meindert Hobbema and Jacob van Ruisdael.

Hobbema’s Woodland Road (1670) has all the hallmarks of a Hobbema: Aerial angle, linear perspective (with your eyes focusing down the road), a building a couple hundred feet off, squiggly Dr. Seuss Lorax trees, small figures, puffy white clouds…

Here’s Gainsborough’s take on the painting:

“Cornard Wood, near Sudbury, Suffolk” (1748) (Image: The National Gallery – London, UK)

Same traits here. Just less-squiggly trees. This is an early work by Gainsborough, and even the painting style is Hobbema. There’s a lot less air in this painting than is typical of a Gainsborough. Even the colors are darker. More earth-toned. The details meticulous. It has the feeling of a Dutch Baroque landscape, and upon first glance, one would not suspect that it’s by the leading light of the English Rococo movement.

Now let’s have a gander at a Jacob van Ruisdael:

“Landscape with Dead Tree and an Oncoming Storm (1649)” by Jacob van Ruisdael. (Image: Musée Fabre – Montpellier, France)

A dangerous natural scene with dark, ominous clouds and a “blasted tree,” often seen in Jacob’s work.

Let’s see how Gainsborough flips it:

Carthorses Drinking at a Stream (c. 1760) by Thomas Gainsborough. (Image: The Tate Britain – London, UK)

It’s a Jacob van Ruisdael, all right, but without the sturm. Or the drang.

Compared to their Dutch muses, Gainsborough’s landscapes are a bit more idealized, the colors brighter, the brush strokes looser but hardly sloppy. There’s a certain daintiness to Gainsborough’s work that’s just lacking in the Dutch catalog. It’s less careful, more spontaneous. And for my money, a little more lively. In this way, despite paying homage to the Dutch Masters before him, Gainsborough puts his own stamp on his landscapes, and it’s no wonder that his work enthralled the likes of John Constable, who lived just sixteen miles from where Gainsborough was born. Together, they made the landscapes of Suffolk famous.

John Constable

A British Romantic painter, Constable painted many scenes of the Suffolk countryside. A mill-owner’s son, he especially loved to paint local waterways. For Constable, unlike the majority of British painters who came before him, the landscape was not the mere background of the painting; it was the star of the show. Painters at the Royal Academy looked down on landscapes, despite demand for them, as wealthy Brits were buying up landscapes by painters like Salvator Rosa, Karel Dujardin, Canaletto, Nicholas Poussin and Claude Lorrain on their Grand Tours of Continental Europe. But Constable offered something different: a uniquely British, not Italianate, landscape.

Here, have a look:

“Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows” (1831). (Image: National Museum Wales – Cardiff, UK)

So how do you spot a Constable? Watch out for paintings at eye-level perspective, with some combination of a river in the foreground, often being forded by oxen or horses, with Salisbury Cathedral in the background. (Rainbows are optional.) This painting happens to have all those things in one neat package!

Look for small human figures, if any at all, in his paintings. He is well-known for his watercolors as well as his oils. He employed a palette knife in his later career on snow and clouds, giving his landscapes a less mannered feel, and putting him on the cutting edge of art (palette knife, cutting edge – get it?!). Have a gander:

Seascape Study with Rain Cloud (Rainstorm over the Sea) (1824-1828) by John Constable. (Image: Royal Academy of Arts – London, UK)

In paintings such as Seascape Study, Constable shifted from Gainsboroughesque, idyllic views of the Suffolk countryside to proto-Impressionist scenes of sea and sky, stepping away from nostalgia for a rural England that was rapidly disappearing in the Industrial Age. He was, just the same, moving away from the centuries-long influence of Dutch Golden Age landscapes (Meindert Hobbema, Jacob van Ruisdael, et al.) into something entirely new – the seeds of modern art. This sudden transition may have found its root in Constable’s rivalry with J. M. W. Turner, the master of atmosphere. But that’s for another time!

Check out more posts like these on the Name That Painter Blog.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections, and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.