Art History 101

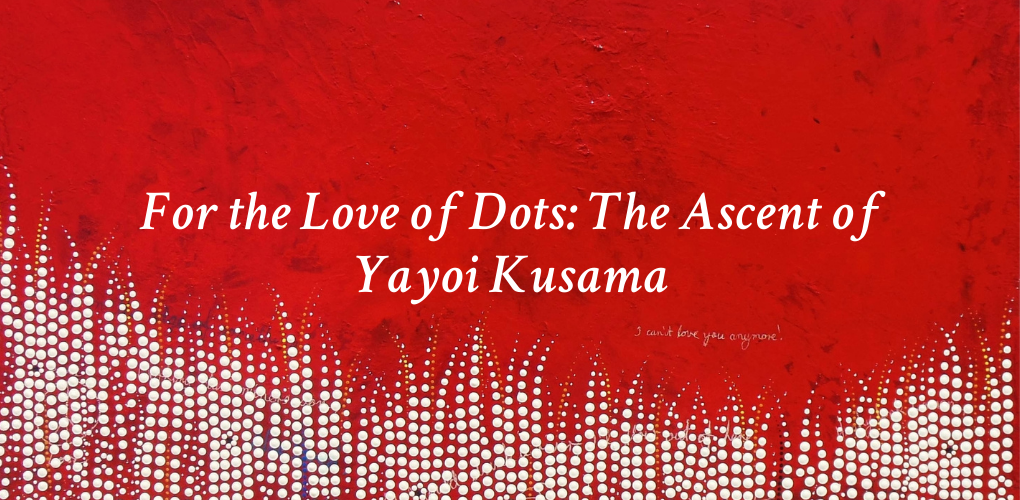

For the Love of Dots: The Ascent of Yayoi Kusama

Yayoi Kusama is an art world super star, with viewers from around the world willing to wait in line for hours to glimpse her installations for timed viewing slots as brief as 30 seconds—just long enough to snap a photo for Instagram, the platform to which much of her popularity has been attributed. Despite this stardom, her artistic innovations within a predominantly white, male art world, and her dogged perseverance in the face of mental illness, have yet to be fully appreciated.

Born in 1929 in the rural town of Matsumato, Japan, Yayoi Kusama began suffering hallucinations as a young child in which dense fields of dots would cloud her vision. To cope, she began drawing these phenomena, but her conservative family did not support her artistic inclinations—her mother even went so far as to snatch drawings away before they were finished, which only strengthened the young Kusama’s resolve. Soon to be 91 years old and now the top selling living female artist, Kusama has taken her dot motifs from doodles to sculptures, fashion, and most notably to her Infinity Rooms, vertiginous mirrored rooms that infinitely repeat her patterns across a dizzying space.

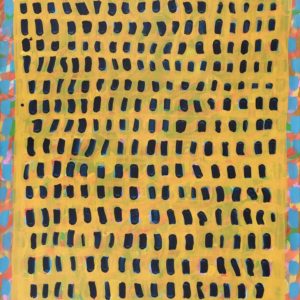

In 1957, at the age of 27, Kusama left her conservative home for New York, with zero connections and a few hundred dollars sewn into her clothes. Shortly after, she began painting her “infinity nets”—meticulous paintings consisting of interlocking loops that would form fields of dots across the canvas’ surface. According to her neighbor, fellow artist Donald Judd, Kusama often worked through the night, completing many of these paintings—the largest of which is 33 feet wide—in one sitting. With their grand scale and overwhelming patterns, these paintings anticipate the immersive environments for which Kusama would become famous.

Many of Kusama’s contemporaries took notice of (and possibly even de facto credit for) her strategies. In the 2018 documentary Kusama: Infinity, the artist claims that Warhol took cues from her repetitive compositions before embarking on his own, most notably after seeing her Aggregation: One Thousand Boats show at the Gertrude Stein Gallery in 1964, in which Kusama displayed a soft fabric sculpture of a boat before a wall of repeating images of the same sculpture. Warhol would debut his iconic cow grid wallpaper at Leo Castelli Gallery two years later. And Claes Oldenberg, who worked primarily with paper mâché before seeing Kusama’s soft sculpture Accumulation No. 1 at the Green Gallery in June 1962, debuted his own sewn sculptures at the same gallery three months later (according to Kusama, Oldenberg’s wife felt compelled to apologize to her at the exhibition). And months after Kusama’s first Infinity Mirror Room installation in 1965, artist Lucas Samaras installed his own version to great fanfare at Pace Gallery.

Samaras’ overt appropriation was the last straw for Kusama: Already prone to depression and isolation, she attempted suicide by jumping from her studio window. But she miraculously recovered and returned to the art world with a bang in 1966 at the 33rd Venice Biennale—although she wasn’t exactly invited. Miffed at Japan’s refusal to include her in their national pavilion, a rouge Kusama filled the pavilion’s lawn with 1,500 metallic balls that infinitely reflected onlookers’ faces. Called Narcissus Garden, the work was part installation and part performance, as Kusama sold each ball for $2 next to a sign reading “Your Narcissism for Sale,” both wryly critiquing the commercialization of art and perhaps foreshadowing the commercial success of her work that would come some five decades later.

Kusama staged similar performances, or “happenings,” across New York City, often incorporating nude performers covered in polka-dots. At the center of the performances was a way for Kusama to explore a recurring philosophical theme in her work: “self obliteration,” or the attempt to dissolve the self, and with it divisions between bodies and the notion of discreet identities in favor of a freeing and fantastical utopia. The polka-dots—and nudity—served as equalizing self-obliterators.

The coalescence of plagiarism, public outrage at her often orgiastic performance art, and the death of her romantic partner Joseph Cornell spurred Kusama to return to Japan in 1973. Following continued struggles with hallucinations, depression, and another suicide attempt, Kusama admitted herself to a psychiatric hospital, where she would reside permanently.

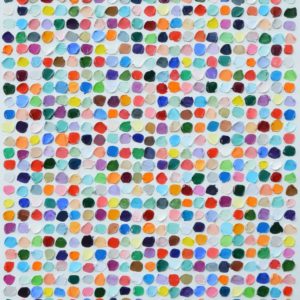

Though resigning to a hospital might ordinarily signal retirement, Kusama’s past few decades as a voluntary patient have been her most commercially successful. Since her admittance, she has developed her most iconic and complex works: In 1994, she made the first of her outdoor sculptures, Pumpkin. In 2002, she oversaw the first instantiation of Obliteration Room, an installation that begins as a white interior that visitors are encouraged to “obliterate” with sheets of round colorful stickers. And her perennially popular Infinity Rooms, with their unprecedented scope and ambition, continue to draw us out of ourselves and towards the infinite.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections, and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.