Art History 101

Art History 101: Minimalism

Have you stumbled across minimalist objects made from industrial materials and wondered how to make sense of what is in front of you? Read on to learn more about the history of minimalism, important artists during the movement and their signature technique and style.

A Brief History of Minimalism

Minimalism emerged as a reaction to the abstract expressionist movement of the 1950s and early 1960s, deriving partly from the reductivism of Modernism and the geometric abstract movement. Many of the art historical movements that emerged in the past centuries, such as Impressionism and Fauvism concerned the invention of new painting styles or new uses of color to better render emotions and “reality”. Minimalism is about art and art itself; rid of any representations, biographies, and expressions. The works and ideas of Russian Supremacist painter Kazimir Malevich in the early 1910s and the ready-made works of Marcel Duchamp around the same time challenged young New York based artists to delve further into the concept of abstraction and what could be considered as art.

In 1959 Frank Stella’s black stripe paintings, featured in the “Sixteen American” exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, became the first works associated with minimal art. Young artists quickly abandoned all unnecessary forms and gestures from their works. In the early 1960s, several young artists based in New York such as Carls Andre, Robert Morris, and Dan Flavin began to work with radically abstracted forms. They strived to challenge and change the way people perceived art objects.

“Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors,” held at the Jewish Museum in 1966, is widely considered as the first minimalist art exhibition. Favorable reviews by critics and academics, features in major newspapers and magazines quickly followed. Minimalism reached maturity in the mid sixties as successful art dealers and influential galleries began showing and representing minimalist artists.

Characteristics of Minimalism

Few artists associated with the movement consider themselves minimalist. The term “minimal” refers to the radical simplification of forms in the works. Having abandoned all representational and symbolic gestures, the final works are often comprised of rigid non-hierarchical geometric planes or forms, relatively monochromatic color palette, and readily accessible industrial and commercial materials. The works convey monumental presence purely through the properties of the materials, sheer size of the arrangements and their occupation of space.

Read on to see how different artists challenged the conventions of abstract expressionism with minimalist aesthetics and techniques.

Carl Andre – Emphasis on Materials

Upon completing military service in 1956 in North Carolina, Carl Andre moved to New York City to pursue art and writing. Prior to joining the army, Andre attended the Phillips Academy in Massachusetts where he met fellow student Frank Stella. Imbued with Stella’s constructivist process, and the works of Romanian modernist Constantin Brancusi, Andre gained the newfound impulse to explore and emphasize the inherent qualities and characteristics of industrial materials, particularly their geometric forms and lines. Andre produced clear solid forms out of firebricks, steel plates and wood, employing only the simple techniques of cutting, placing and stacking his materials. Thus, Andre emphasized and preserved the natural textures and properties of the materials. There is an undeniable presence to Carl Andre’s sculptures, some extremely thin and horizontal, and many monumental in size. Andre’s sculptural works redefine and, in a sense, reorganize the space they command. Andre precisely summarizes the production process and the designated experience of his sculptures: “Rather than cut into the material, now I use the material as the cut in space.” (Cuts: Texts 1959-2004, Carl Andre and James Sampson Meyer, 2005)

Dan Flavin – The Neon Lights

Iconic for his use of fluorescent light tubing, Dan Flavin’s neon fixtures are instantly recognizable in museums and galleries. Flavin began using light as a medium in 1964, and focused on the effects of permeated light in space. Much of Flavin’s work celebrates the artistic ideologies of constructivism from Russia in early 20th century, as well as abstraction theorists such as Theo Van Doesburg. With a single light tube as the basic property of his art, Flavin’s works progressed from wall installations to massive architectural structures. His works are composed with minimalist characteristics, such as repeated simple geometric shapes and easily accessible industrial materials. The diagonal hang not only denies gravitational stability and the materials’ functionality, its trajectory also disrupts the linearity of conventional interior spaces, thus alters one’s perception of the room.

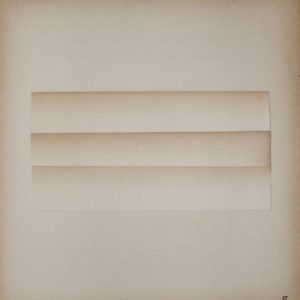

Agnes Martin – The Iridescent Grid Canvases

When asked about her art, Canadian born artist Agnes Martin replies, “Nothing in this world applies to my art. Its beyond the world. I paint about happiness and innocence and beauty.” In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Martin completely relinquished any abstract expressionist tendencies from her style, resulting in her carefully calculated grid marked paintings. Although Martin resigned from painting for many years due to schizophrenic episodes that occurred during her 40s, her finished series convey a strong sense of sincerity and balance between matter and emptiness. Though the grid patterns may seem singular- even controlled-the possibilities of the grids are, in fact, infinite. To help a viewer understand the “emptiness” of her canvas, Martin uses the analogy that a beautiful rose out of sight behind the wall is still known as a beautiful rose; her gleaming canvases are a wall that serve as a conduit for people to experience the beauty and innocence in this world. (Christie’s, June 2, 2015)

Donald Judd – The Stacks

Donald Judd launched his artistic career as a painter around 1948 when he was acquiring a philosophy degree from Columbia and attending classes at the Art Students League of New York. By the early 1960s, Judd began to produce three dimensional works, declaring that “color could continue no further on a flat surface… Color, to continue, had to occur in space.” (Judd Foundation, 2016). Though a major figure in the minimalist movement in the 1960s, Judd described his finished works comprised of stacks, boxes and assemblages as “Specific Objects” rather than minimalist. The stacks are possibly the most recognizable of Judd’s expansive oeuvre, which came to redefine post-war sculptural practices in America. The finely finished stacked forms hang weightlessly on the wall as paintings would, yet the carefully spaced out forms allude to no symbolic meanings other than a sense of industrial production assemblies.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.