Art History 101

5 Modernist Women Sculptors You Should Know

“At no point do I wish to be in conflict with any man or masculine thought. It doesn’t enter my consciousness. Art is anonymous. It’s not competitive with men. It’s a complementary contribution.” –Barbara Hepworth

While you may be familiar with the work of Auguste Rodin, Constantin Brâncuși, and Alexander Calder, and a plethora of other sculptors of the male persuasion, female influence over the medium has been substantial – and remains so. Here are 5 modernist women sculptors you might not know about, but definitely should.

#1: Barbara Hepworth (born 1903)

An unequivocal leader in 20th century Modernist sculpture, Barbara Hepworth established herself as a major female figure in a man’s world. A survey of her life reveals an impressive list of accomplishments and contributions to art far and wide. After studying on scholarship at the Royal Academy of Art, Barbara spent years traveling Europe, developing her craft. There she found love; she found art movements. She was involved in Absraction-Création in Paris as well as the Unit One movement, both aimed at spreading awareness and interdisciplinary collaboration among Modernists and Surrealists. Alongside her husband, painter Ben Nicholson, and a handful of other artists, Hepworth paved the way for Constructivism in Europe during the Post-War period, weathering the restructured social climate and continuing to shape the Modern art aesthetic. She was awarded the Grand Prix at São Paulo’s 1959 Bienal, and spent her later years teaching and supporting emerging artists.

#2: Eva Hesse (born 1936)

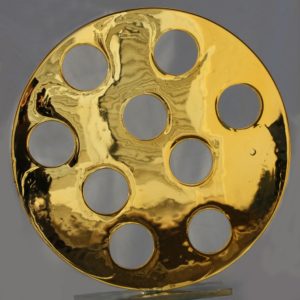

A key figure in establishing the postminimalist art movement of the 1960s, Eva Hesse reinvigorated modern sculpture with new use of materials such as latex, plastics, and more. As a growing Nazi sentiment spread in her hometown of Hamburg, Hesse and her family were forced to escape growing danger and persecution, fleeing to New York. Her new life in New York continued to see tragedy, first when her parents split, then her mother’s subsequent suicide when Eva was 10. However, her younger years were also spent finding her love of art, an avenue she turned to in helping her cope with her mother’s tragic passing. She studied at various institutions, including Pratt and Cooper Union, eventually landing at Yale University to study under Josef Albers, graduating in 1969. Inspired by the Abstract Expressionists, Hesse created thickly impastoed paintings and corporeal object-like sculptures she exhibited at Brooklyn Museum. During this period she met sculptor Tom Doyle, who she would marry in 1962, and befriended artist Sol LeWitt, whose geometric style would greatly influence her practice. Hesse returned to Germany for a brief period and began experimenting with plaster and string to make her subtly provocative Ringaround Arosie (1965). Her return to New York saw the end of her marriage and marked a distinct turning point in her artistic career, focusing solely on sculpture and pioneering the use of new materials. In Schema and Sequel (1967-69) Hesse brushed layer upon layer of latex to create rippled, molded circles. Her Accession series features cubes of metal turned into soft looking bristles. Her later works were highly acclaimed both during her lifetime and after, included in prestigious and influential museum and gallery shows of the late 1960s. Her flourishing career was cut tragically short after she lost her battle with a brain tumor in 1970 at the age of 34. Hesse’s innovation in abstract art and forms continues to inspire artists working today.

Whether intentionally or not, Hesse’s materials lack permanence; their deterioration has prohibited much of her work from exhibition. However, Expanded Expansion can be seen at the Guggenheim in New York.

#3: Camille Claudel (born 1864)

Camille is perhaps best known as the tumultuous lover of Auguste Rodin, however her artistic talent should speak for itself. Born in France as the eldest of three children, she developed an affinity for molding clay at a young age, sculpting portraits of her family members she persuaded to sit for her. She moved to Paris to study at the Académie Colarossi, first under sculptor Alfred Boucher, then Auguste Rodin. Rodin was impressed with Camille’s artistic skill and passion, and was inspired by her beauty; they soon embarked on a symbiotic relationship of mutual artistic inspiration and romance that would last for years. The Rodin period of her life saw tremendous growth as a sculptor, as well as a budding trauma that would plague her later years. Though the extent of Claudel’s hand in some of Rodin’s most celebrated works is disputed, it is likely her influence was substantial. Along with assisting him on The Gates of Hell and Burghers of Calais, Claudel completed masterpieces of her own, namely The Waltz (1893). The nature of her and Rodin’s relationship continued to deteriorate, as he refused to leave his wife for her, and the two eventually split, leading Claudel into a state of both tremendous creativity as well as despair. She sculpted tempestuous love triangles out of onyx, such as La Vague (1900), soon falling into a reclusive and paranoid state, refusing to leave her studio. Claudel’s family became increasingly worried about her health, and committed her to an asylum– a decision she was helpless against. Despite insistence from doctors and Claudel herself, her family insisted she remain in the asylum, where she eventually died after 30 years.

Her sculptural works can be seen in the permanent collection at the Museé Rodin in Paris.

#4: Lygia Clark (born 1920)

Brazilian artist Lygia Clark’s multi-disciplinary practice blurred the distinction between artwork and viewer, inviting audience participation as an integral part of the work. Her sculptures function as a physical piece and representation of her ethos, offering viewers another tangible form to shape a unique experience with. Born in Minas Gerias during a politically tumultuous period, Clark’s artistic practice developed while Brazilian art began to first see a move toward abstraction and Constructivism. She studied painting in Rio de Janeiro before relocating to Paris to study under modernist artist Fernand Léger. She moved back to Brazil in the 1950s and began to create under a new form of abstraction she called Neo-Concretism, which focused on a form less material and rational. Her Bichos or “Critters” sculptures are organic forms that reveal the joints and hinges that keep them together, distinctly drawing attention to what is generally covered up. The Critters’ exposed exoskeleton was also a variable component, inviting the audience to change their form, and challenging the notion that sculptural viewing is fixed and singular. She left Brazil for Paris to teach at the Sorbonne in 1970, and began to experiment with Art Therapy and the potential effect art had in healing viewers. After returning to Rio de Janeiro, Clark spent the rest of her career diving deeper into this concept and creating works that relied on elements such as smell or saliva (Baba Antropofágica) rather than sight to establish physical connections. For Relational Objects, Clark built various wearable objects that connected two individuals suffering from psychological problems, relying on the invisible presence between them rather than physical touch. After years of treating patients with art, she died from a heart attack in 1988.

One of her Bichos sculptures can be seen at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.

#5: Niki de Saint Phalle (born 1930)

Born in a town near Paris to a traditional family, Niki de Saint Phalle turned to art as a means to express her discontent with the conservative life she had fallen into. She created paintings and sculptures that reflected on a greater presence of women in the world, as buxom and joyful beings content with themselves, and vastly contributed to expanding the proliferation of public works worldwide. Saint Phalle spent her teenage years modeling, dictated by what her family expected of her – at eighteen she graced the cover of Life and married her first husband, writer Harry Matthews. Her growing disillusionment with domestic life would lead to a nervous breakdown, after which she turned to painting as a therapeutic outlet. Untrained in art, Saint Phalle found mentorship and support in close artist friends, such as painter Hugh Weiss. She spent the next decade experimenting with oil paints and their application, developing what she called “Shooting Paintings” wherein paint balls were shot at a canvas though a gun. In the 1960s she began to explore the archetypal role of women, creating a series of sculptural figures called “Nanas.” The Nanas were crafted from papier-mâché, yarn, wool, and wire, as envoys of women in the new age. In 1979 Saint Phalle embarked upon her largest project, a “Tarot Garden” in Tuscany featuring multiple female sculptures representing the figures found on tarot cards. She spent her later years making more public works, including a redesign of the Stravinsky Fountain at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris.

Nike de Saint Phalle’s works can be seen throughout the world, including Escondido, California, Royal Herrenhäuser Gardens in Hannover, Germany, and at the Hakone Open-Air Museum in Japan.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.