One to Watch

Oliver Curtis’ photographs explore the unexplored

Oliver Curtis’ photographs explore the unexplored

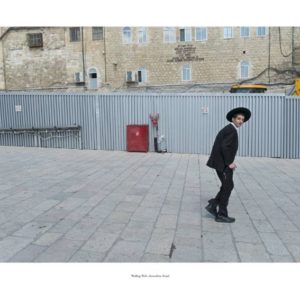

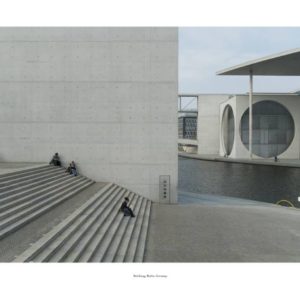

Oliver Curtis offers a new approach to depicting the unexplored. His Volte-face project consists of images taken at some of the world’s most visited monuments and sites–with his back turned to them. Oliver focuses on the seemingly banal, instead monumentalizing an empty plaza, a patch of dirt, or a crowd of people with phones in hand. He is interested in capturing the familiar from an unexpected point of view, be it by choosing unfamiliar subjects or deconstructing them into a series of abstracted forms.

Oliver studied photography at Filton Technical College in Bristol and film and television at the London College of Printing. He had his first solo exhibition, titled Volte-face, at London’s Royal Geographical Society in 2016. Oliver also works as a cinematographer and has contributed to numerous documentaries, feature and short films, experimental gallery-based installations, and commercials for clients including Coca Cola, Sony, Guinness, and Canon. He has been featured in numerous publications such as National Geographic Russia, National Geographic Poland, Conde Nast Traveller Spain, BBC Radio, Financial Times, and DW – TV Euromaxx Berlin, National.

What are the major themes you pursue in your work?

My photographic practice varies enormously in style and subject, but what I think unifies it is an interest in depicting the unexplored. And by that I don’t necessarily mean exotic landscapes that haven’t been photographed before, but more capturing the familiar from an unfamiliar or unexpected point of view. The Volte-face project encapsulates this – turning my back on some of the most photographed places on the planet to record the view no one else is looking at. In contrast to this, London Conversation depicts familiar views in my own town in a deconstructed, abstract way rendering the everyday as a series of textures and impressions.

How did you first get interested in your medium, and what draws you to it specifically?

I remember being given a Box Brownie camera as a child and being fascinated by the inverted image on the ground glass viewfinder. I became enthralled by the idea of looking indirectly at things, with light mediated and distorted. That for me is the very essence of photography; a process of capturing verisimilitude, of fixing a likeness of an object, landscape or person, and yet the image created is a wholly new thing in its own right detached from the thing it is supposed to represent.

How has your style and practice changed over the years?

I would say that my photographic practice is still in its infancy since I have spent the greater part of my professional life working as a cinematographer. Consequently I am still open to exploring new directions and different photographic formats. But what photography gives me, in contrast to my work in film and television, is a very personal form of expression without the pressure of a script or schedule to follow.

Can you walk us through your process? Do you begin with a sketch, or do you just jump in? How long do you spend on one work? How do you know when it is finished?

The Volte-face project took four years to complete. My aim was to visit as many of the most visited and therefore photographed places on the planet and discover a view at each of them that revealed something new and unexpected. In every instance I hoped to reflect some aspect of history, ancient or recent, that one might associate with that particular site. Occasionally, my take would be very personal, reflecting my mood or thoughts at the time (at Buckingham Palace, for instance). In other situations, a composition would present itself (such as the Lincoln Memorial in Washington DC) which seemed to engage in a really specific way to the history of that monument. These visits would typically take 3 to 4 hours, but one or twice I would return multiple times over a period of days until I found a shot which seem to encapsulate my feelings about the place.

What are some of your favorite experiences as an artist?

During my first solo show I tried to be in the gallery as often as I could. Receiving feedback in person was a revelation. With filmmaking, one is so often distanced from the moment of consumption. But to be around people as they saw my images for the first time was fascinating and illuminating.

What was the best advice given to you as an artist?

With reference to the choice between fixed focal lenses or zoom lenses: “If it’s too close, step back. If it’s too far away, move closer.”