One to Watch

Martina Grlić’s photorealist paintings monumentalize the past

Martina Grlić’s photorealist paintings monumentalize the past

Croatian artist Martina Grlić is fascinated with history, both personal and shared. She depicts scenes of everyday life in former Yugoslavia, ranging from men and women working in factories to monumental still lifes of children’s toys, in her photorealist paintings. Martina is interested in the strong emotional reactions viewers have to these works, which range from nostalgic to political, and how these reflect changing values in society.

Martina received an MA in painting from the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb, Croatia. She is the winner of the 2012 Erste Grand Prix for Best Painting and completed a residency at Glo’art in Belgium in 2014. She has since shown her works in numerous solo and group exhibitions internationally, in countries including Croatia, France, China, and Poland. Most recently, she had a solo show at Simulaker Gallery in Slovenia and group shows at the 51st Zagreb Salon, Croatia and the National Museum in Gdanjsk, Poland.

What are the major themes you pursue in your work?

All of my series are focused around history and memory. I am fascinated by how the events which took place in the near past shape the world we live in today. Basically, through my paintings, I am trying to understand the society I live in.

In my Factory series, I choose scenes of production with working men and women from the big factories of former Yugoslavia. Some of these factories disappeared during transition and were destroyed prior to the privatization process during the 90s. Changing ideologies which result from political turmoil, particularly changes in the attitude towards work and how it directly affected the production of value in society, is what initially interested me.

There is a certain ideological power that these images embody. The scenes are from the time when work was glorified and was considered important. Through factory labor emerges a figure of heroic men, and especially women, who became a pillar of socialist society and gained respect. Interesting is the reaction of the observer as these scenes trigger certain emotions which can be political or gendered, and to many they represent nostalgic memories.

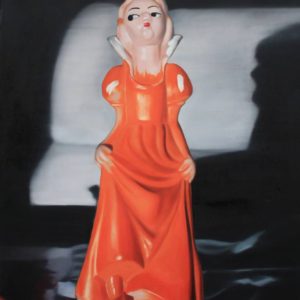

My works BadelBrandy and Čungalunga are part of a series of paintings named Product. The idea was to explore a cultural and living space through the separation of certain elements from the past. Popular culture of the region in the period of the last fifty years has remained inarticulate, and it was impossible to collect all the data in order to make a scientific approach to the matter. So I started from my personal memory. By painting the subjects I recall personally, I wanted to show how everyday objects can influence the identity of the individual. When placed in the context of the gallery, deprived of their initial function, these objects clearly show the change in the way society produces its values.

What was the best advice given to you as an artist?

Don’t give up and take time with your palette.

Prefer to work with music or in silence?

I prefer to work with music, although this changes from time to time. I never mind a little Chopin.

If you could only have one piece of art in your life, what would it be?

Perhaps some grand painting from Velasquez or some late piece from Julian Schnabel. It’s a hard question. There is more than one piece of art I wouldn’t mind having. Maybe what I like most is to have a piece from a colleague I know personally and whose work I admire.

Who are your favorite writers?

At the moment, I am reading a lot by Paul Auster, although I am more of a movie person.