One to Watch

Laura Foster Nicholson: Weaving Awareness

Laura Foster Nicholson: Weaving Awareness

American textile artist Laura Foster Nicholson creates beautiful artworks that address the environmental impact of modern industrial practices. Laura received her MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art and has been regularly exhibiting her work since 2013. Keep reading to learn more about her background, process, and inspiration.

Tell us about who you are and what you do. What’s your background?

I was born into a family of creative people on both sides. My parents were born in the 1920s, and neither could pursue their deepest wishes because of the Great Depression, the Second World War, social norms, and, upon marriage, needing to raise a family of four children. My father would have been an engineer, but after the war, he acquiesced to making a living as an accountant, though he was happiest in his small wood shop. My mother’s family was all creative, so she went to an art academy with her parents’ blessing, But real work for her was secretarial. They were totally supportive of my decision to go to art school and saved every drawing I made as a child.

What does your work aim to say? What are the major themes you pursue in your work?

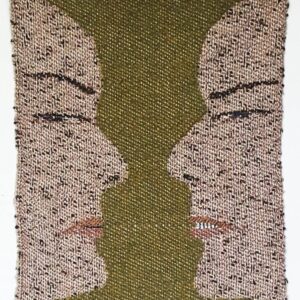

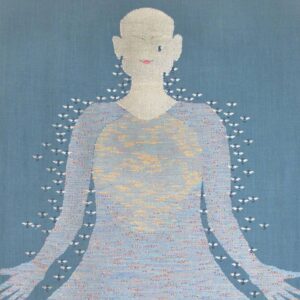

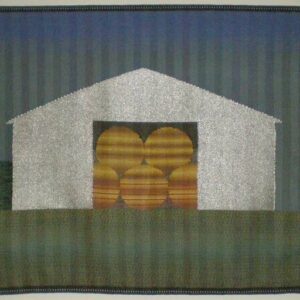

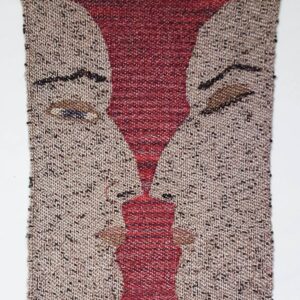

My textile work has long been about using the architecture of the weave structure to build a different way of expressing my vision for formal gardens, architectural studies, domestic dwellings, and layouts of rural landscapes and buildings. In 2020 I began using my vision to explore and describe the dramatic effects of climate change on these environments. I began with the flooding of Venice, to grieve and mull over the ruination of an extraordinary city as a result of long-term sea level rise. I have also opened my senses to what the industrial farming landscape engenders: clearing of forests, flattening lands, and massive use of chemicals among sturdy and simple buildings.

Can you walk us through your process for creating a work from beginning to end?

When an idea enters my head, it may come from something that caught my imagination in the landscape or from images I have seen online in my research. After studying the subject, I map out the composition while preparing the loom to weave the image. I have chosen weaving as my main art-making medium for reasons of personal satisfaction as well as its expressive capability–and I love the challenge of translating an image into a textile. Then, I weave the image, row by row, free to alter as necessary.

Who are your biggest influences, and why?

My professors in art school: Warren Rosser, for exacting the concept. Stephen Sidelinger, for opening my mind to the relationship of pattern and image layout to textiles. Gerhardt Knodel, for his keen vision, sharpening my focus and enhancing my commitment to textiles. Also Architect Aldo Rossi, for introducing the idea of light and mood to me. Designer William Morris, for his understanding of the difference between the textile surface and the painted surface. Painter Eric Ravilious, for his beautiful and yet tragic depictions of war in the British countryside.

How does your work comment on current social and political issues?

My current work explores the subject of climate change, both through images of disaster and through passive images of environmentally destructive practices, like industrial farming.

How do you hope viewers respond to your works? What do you want them to feel?

I have always valued beauty as an excellent way to entice the viewer to regard my work. In current work, as beauty compels interaction, the discord of image and subject matter becomes apparent.

If you couldn’t be an artist, what would you do?

I would be a writer. I enjoy working with language and articulating thoughts. I kept a blog for a number of years, which gave me a very satisfactory way of talking about the themes in my artwork or my general thoughts about a creative life.

What are some of your favorite experiences as an artist?

In 1985, I entered the Venice Biennale of Architecture with a series of tapestries based on a villa in the Veneto. I was thrilled to find my artwork was accepted in a competition for architects, and I won one of ten Stone Lion awards. I also had a residency at Bloedel Reserve in Washington in 2016. Amid a glorious forest of trees, I became bewitched by things like the eyes peering at me from alder trees, the moodiness of the rain and light, and the Mycorrhizal network.

What was the best advice given to you as an artist?

One: Never stop at what is easy–push for conceptual depth. Two: Learn how to depict subject matter in textiles. A textile is not the same thing as a painting, and the media demand separate ways of understanding space.