One to Watch

Naomi Kaempfer on Human Connection in a Post-Pandemic World

Naomi Kaempfer on Human Connection in a Post-Pandemic World

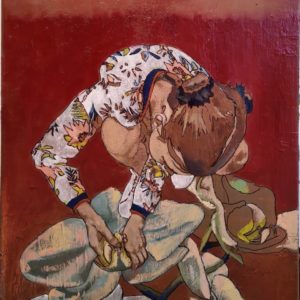

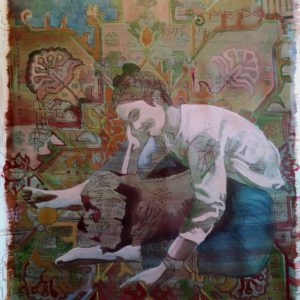

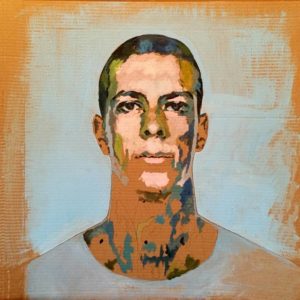

For Antwerp-based painter Naomi Kaempfer, the human face is like a landscape, reflecting one’s history, emotions, thoughts, and desires across alternating passages of clarity and confusion. With an interest in how much of ourselves we reveal to others and how much we consciously (or unconsciously) conceal, Naomi captures the tension between the visible and invisible through enigmatic portraiture.

With delicate linework, textural warmth, and careful compositions—which are often left partially unfinished—Naomi’s figurative paintings offer the viewer a window into intimate encounters and quiet narratives. Often painted on cardboard, the fleetingness of these moments—and the human face itself—is heightened through the material’s inherent disposability. In a post-COVID and digitally saturated world where human connection has become fraught and uncertain, Naomi’s paintings are all the more resonant, inviting us to explore how we engage with the world around us, with others, and with ourselves.

As a creative director working with 3D printing, Naomi has led projects in collaboration with museums, designers, and artists around the world, with collections exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Tell us about who you are and what you do. What’s your background?

My name is Naomi Kaempfer. I am a painter and a creative director specializing in 3D printed art, design, and fashion. I was born in Boston to Dutch scientists, grew up in Jerusalem, and currently live in Antwerp, Belgium. I studied philosophy and art and have a master’s degree in design from the Design Academy Eindhoven. I began painting at a very young age, starting my own personal search for truth, beauty, and humanity.

What does your work aim to say? What are the major themes you pursue in your work?

I primarily focus on portraiture. Our faces are landscapes reflecting interaction, exchange, contemplation, daydreams, feelings, and the spontaneous tension between the visible and the invisible. Now in the time of the pandemic, more than ever, I am excited by the intimate, vulnerable expression of our faces and also the questions they raise. How often do we convey more than we wish, more than we’re aware of? How much of ourselves, our history, our thoughts, our emotional depth, do we show? Feel allowed to show? How do we carry ourselves in our day-to-day lives?

I love playing with the tension between the finished and unfinished surfaces in my paintings. I like to reveal the plain cardboard or stitched canvas that lies beneath the thick layers of oil paint. To reveal the layers below our makeup and social masks.

Can you walk us through your process for creating a work from beginning to end?

I start my portraits with a model, either working directly with them or a photo of them that captures movement and a special moment. The next step involves making a study, and I sketch out my work on pieces of old cardboard boxes. I love the warmth of the brown color and the way the paint is quickly absorbed by the thirsty fibers. Sometimes I stick with the cardboard box, and other times, I select a new substrate for the final piece. I like to play around with different surfaces but frequently use canvas or stitched canvas. I use pens or permanent markers to make an outline and then apply oil paint, some of which has been thinned out, so there is a transition between more naive contemporary illustration and deep tones and heavier masses of rich oil paint. I look for the tension between treated and untreated surfaces, naked and covered areas.

Who are your biggest influences and why?

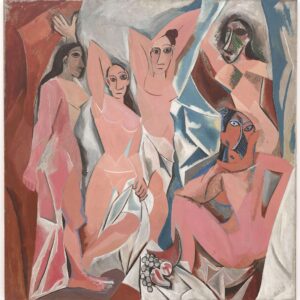

A few of my favorites are Francis Bacon, Gerhard Richter, and Euan Uglow. I love Bacon’s expressive dynamics, his intensity, and almost violent portraiture combined with his well-balanced interiors and the rawness of bare canvas. With Richter, it’s his photographic realism, his early abstracts and their color splashes, and his studies into the materiality of color flow—layering, smearing, covering, and uncovering. Uglow’s work has an old master’s tension between the mundane, a simple setting with exposed flesh, and an attention to detail. His surfaces seem engineered, analyzing the 3D edges of the body with knife-like, measured pencil markings.

How does your work comment on current social and political issues?

As my parents are Holocaust survivors, I often struggle with my own history and their inability to fully understand and release the deep emotions of their experiences. I believe we all carry unfinished business that becomes a lifelong journey to unwind, digest, and come in touch and terms with. As the pandemic has done, I hope my paintings also highlight social questions about the human ability to connect with others, as well as with ourselves. How much of our history and inner layers are we willing to discover and accept? How much do others want to see and accept?

How do you hope viewers respond to your works? What do you want them to feel?

I am happy if my paintings cause an emotional response in viewers. It doesn’t matter what the specific feelings are. I’m also happy if viewers are interested in discovering the hidden and invisible parts of my paintings: the texts and symbols inside the paint layers and the images beneath. I think that a good painting is one that matures with its audience, that quietly keeps speaking, interacting, and confirming.

What are some of your favorite experiences as an artist?

Creating a painting can be a very frustrating experience, a sort of fight with an ideal image that is struggling to be born. One of my favorite experiences is when I stop fighting and just surrender, allowing the energy and the grace of the unexpected magic to come through.

What was the best advice given to you as an artist?

Making a great painting requires two people—the one who paints and the one who will shoot the painter so she stops. There is a very thin line between a painting that is done and one that is overdone. The “umami,” or essence of deliciousness, is created by leaving gaps and unfinished business.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections, and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.