Art We Love

The Essence of Being: An Interview with Artist Miguel Laino

Discover some of the art that’s catching our eye lately. In this series, we’ll bring you the stories behind some of today’s most fascinating works of art, straight from the mouths of their creators.

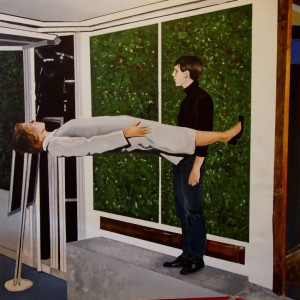

To observe Miguel Laino‘s work is akin to entering another realm of consciousness, a world wherein forms and objects are free to move and change freely. Featured as a Saatchi Art One to Watch and Artist to Invest in, Laino is originally from Spain, relocating to London in 2001 to study women’s fashion at Central Saint Martins before turning to painting as a means of reflecting on and representing his observations of the world. The self-taught artist is thus informed by his own impartial perceptions filtered through a philosophical rendering of how beings exist, free of hierarchy and permitted to change with ease. Laino’s paintings are like a visual exploration of the Aristotelian study of “being qua being,” meaning being for the sake of being in the primary sense of the term, aiming to capture the attributes and fleeting moments of these forms’ true spirits and essences.

Further drawing upon metaphysical concepts, his subjects—whether conceptual or material—obey a different set of rules, or rather lack thereof. Bodies are free from the fixed confines of gravity, allowed to droop, multiply in parts, and blend into their surroundings, often manipulating their body schema in front of the viewer’s eyes. In a recent painting entitled Disillusion & Dissolution, the only thing concrete is change and upheaval itself, grounded by the observing monks’ total acceptance of the momentary tumult. A female form floats among upturned tables and chairs, blurring the distinction between the two. The unseen force of Disillusion & Dissolution is the acceptance of inevitable chaos and entropy in this world. In this sense, each viewer can embody the monks, their calm acceptance suggesting how we might deal with it.

Read our Q&A with Miguel below, in which he discusses his work.

A prominent feature in Disillusion & Dissolution is the presence of the monks, which the viewer might not identify as monks had you not explicitly pointed this out in the work’s description. What is the significance of this specific choice for you, and what is their read on what’s happening in front of them?

The title itself refers to relatively well-known concepts in Eastern philosophy and mysticism, which would already key some viewers in to the subject matter. Artwork statements can be a double-edged sword in some respects, as mystery and interpretation are intrinsic aspects of experiencing art. To strike some balance, my statements offer my own response to that mystery… one possible interpretation. But that should not limit the viewer’s perception—rather it should open an ongoing dialogue between artist and audience—between all of us. What is key is that I too am interpreting the work after the fact of its creation. It’s a discovery process for the artist, as well.

There are many parallels between artists and monks: the solitude of the practice, the meditative focus required to tap into primal creativity, the non-judgmental observation of beings and phenomena. Perhaps this is why these source images appealed to me, but it was not a conscious thematic choice aimed at telling a particular story. My view is that the monks are unaffected by what they see. They are immersed in the source out of which the forms arise and to which they return. This frees them to observe the passing show with unconditional love, all the while seeing the eternal essence, which is animating the temporary forms. They are “dis-illusioned,” but not in a negative sense. They are free of the illusion that happiness comes from an external source… that we can get it from outside things. They realize it is a natural part of their very being, which is ultimately connected with everything. There is no “other”—observer and observed are one.

It appears that a recurring motif in your work is an emphasis on or the exaggeration of limbs. Hands are pointedly expressive or enlarged, arms heavy and dangling. In Disillusion & Dissolution the female figure has 2 extra legs, which you’ve equated to an “overturned tortoise or beetle.” What do you aim to achieve with this choice?

This could be said to depict the helplessness of beings trapped in identification with form, with their bodies and personalities, social status, achievements etc. All things which absorb so much of our time and energy, but which must ultimately desert us in the design of things in this dualistic dream. If you believe you are your body and you know the body is temporary, fear is inevitable and freedom is impossible; joy is always tainted with unease. Another way of looking at it is that consciousness is like an empty room and beings and phenomena are its furnishings. From that perspective, the female figure becomes an overturned table.

Many of your paintings feel like expressions of familiar experience that have crossed over into a murkier, dreamlike state, with forms interacting in alien ways. How much do you rely on the surreal to reflect a more general experience or to explore metaphysical themes?

Broadly speaking, painting, or any other creative pursuit, perhaps any sentient pursuit, is an exploration of reality—a search for truth and meaning. At some point in that journey we begin to question the certainty of familiar things as it dawns on us that only change is constant. If we are moving about in a world that is constantly changing, yet treating things as solid and certain, are we not “dreaming” in our waking lives? Perhaps dreams are as real, or more real?

Again my work is not intentionally surrealistic, but the way I try to express that interplay between the animating essence and changing forms of things seems to produce an effect that is perceived as surrealism. It depends on your viewpoint. If you believe the material world to be fixed and unchanging, then surrealism is bizarre. If you believe in metaphysics or quantum physics, you realize it is all about probability, potential, uncertainty, mystery, and constant change. From that viewpoint everything is equally ordinary and equally bizarre, there is no hierarchy.