One to Watch

Gala Bell’s Unconventional Methods and Transformations

Gala Bell’s Unconventional Methods and Transformations

Gala Bell is a multidisciplinary artist whose practice cultivates two strands of making—one honoring tradition by embodying precepts of classical and baroque, and the other seeking to disrupt it. Using unconventional materials and methods usually found in a kitchen, Gala transforms her studio into a lab of material transformation, creating busts made of sugar and deep-fried paintings. Gala holds an MA in painting from the Royal College of Art in London and a BA (Honors) in fine art from City & Guilds of London Art School. She has exhibited in multiple museums and galleries, including The Victoria and Albert Museum in London, The London Design Festival, The Design Museum in London, the Korean Cultural Institute in Berlin, and Galerie der HBKsaar in Saarbrücken, Germany.

Gala was commissioned by BBC One and Tate and Lyle for her sugar sculptures, with a piece acquired by the Tate and Lyle Museum archive in London. She was shortlisted for the Ashurst Art Prize in 2021, featured in Sotheby’s Made in Bed Magazine, Dazed, Art Reveal Magazine, and interviewed on the To The Studio podcast.

Tell us about who you are and what you do. What’s your background?

I am an artist working in painting and sculpture; my practice flips between traditional and unconventional techniques and is currently growing to encompass social practice. I grew up in London, and my studio is based here, although I travel often and have created work abroad.

What does your work aim to say? What are the major themes you pursue in your work? Can you share an example of a work that demonstrates this?

My attitude to art is one of experimentation and exploration. The main subjects in my work consider light, alchemy, transformation, and colour as a recipe or material that can embody those ideas. My painting always takes on a metamorphosis from figuration to abstraction, testing pigments to understand how one can illuminate and the other can cast a shadow, a balance between glowing, coming forwards, or falling into a recession.

My other installation work, such as the sugar sculptures or fried paintings, also looks at luminosity, transparency, and the passing of light, particularly in association with liquids, gels, or semi-transparent materials. I am interested in how we categorise, classify, and understand the world through value—a system we have created that places certain materials above others due to rarity, the difficulty of extraction, time and labour, beauty, or narrative. The installation work using food explores those themes in relation to taste and class distinction, blurring the boundaries between hierarchies.

Can you walk us through your process for creating a work from beginning to end?

Usually, my process begins with a collection of written thoughts, images, and a drive to discover something—usually about a material or subject and how it can create an image or object. Wandering, looking, and uncovering is the best place to be; it is like seeing for the first time and being curious about where something has come from, what it consists of, and how it behaves. When I am painting, I will often have some keywords in mind. I have a box of cut-up pieces of paper with text and phrases that I have found interesting as future titles or directions for drawing. For example, in ‘Coil for Defence,’ I was looking at spiral forms within the body/nature, the idea of a defence mechanism both as psychological or as an armour or weapon.

Maybe I will look at historical heroines or female warriors or forms/fossils of animals that take on that role… it will be many things that, in the end, will create a synthesis of all these things. The finishing point is usually abstract at first glance, but the more you spend time with the forms you will see that the work retains some elements of these initial ideas. In order to begin drawing, I have to draw something particular, figurative, that has an intention and is something that I can respond to. From there, with time, it will evolve on its own.

Who are your biggest influences, and why?

Of course, I love so many artists, but after so much snobbery from the institutions, I have settled on more subtle interventions. For his performance work, Francis Alys is one of my all-time favourite artists. His work encompasses so many challenging socio-political aspects of the people he works with. Still, he is so skilful at condensing the work into a single act or idea where the delivery is optimistic, emotional, and genuinely inspiring. He does a lot of work with children, based around games, which gives his work an optimism, sincerity, and innocence that is magnanimous.

I have just seen hundreds of artworks at the Venice Biennale, and they were pants compared to what Francis Alys showed. He is selfless. Shimabuku is another favourite of mine, and he also creates these subtle but poignant interventions that are at once comedic and heart-breaking, tinged with a beautiful Japanese sadness. I particularly love the work ‘Do Snow Monkey’s Remember Snow.’ Camus is also influential, particularly in his manifesto ‘Create Dangerously,’ as is Sartre’s ideas on ‘le visquex’.

How does your work comment on current social and political issues? How do you hope viewers respond to your works? What do you want them to feel?

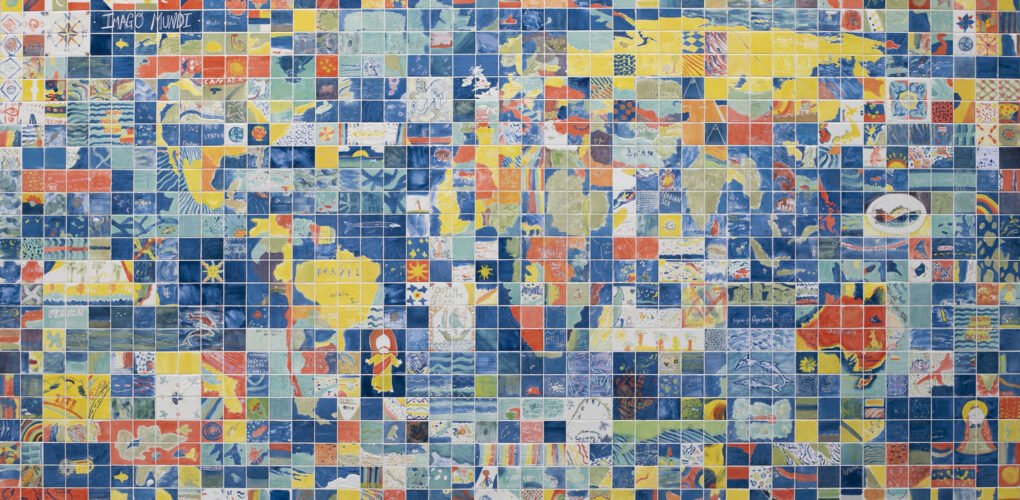

My latest work, ‘Imago Mundi’ speaks about union, borders, migration, inclusion, and community. Art is activism. Maps represent a place; they trace a complex history of migration, trade, and changes to land and territories. New generations create changes that continually shift our readings of the world map. It was only after the 80’s that we had our first photo of the world taken from outer space; before that, maps were all drawn by artists, sometimes combining ideas of the spiritual with empirical cartography.

The first drawings of the world come from Babylon, carved into a clay tablet. We have ‘Imago Mundi,’ our first image of the world in the 9th Century BCE. Working with a youth group and a community centre, we managed to pull off a laborious project creating our own interpretation of a world map. The work is a large ceramic tile mural featuring 1,035 tiles hand painted by children in the local community at Hogarth Centre and a charity called West London Welcome, helping individuals who have suffered a breach of human rights or who may be fleeing their home. The wall is a permanent fixture, and it’s a permanent mark that says ‘we are here’—each of them with their unique characters, stories, and experiences. Our environment is under strain; anarchism is on the rise. ‘Imago Mundi’ is a moment to celebrate the union between people; it is made by a collective, where they shared positive moments and were able to mark their territory, where they could change something, and where they had control.

What was the best advice given to you as an artist?

Be comfortable with failure—you need to persevere in order to own your craft.

If you could only have one piece of art in your life, what would it be?

The stone reliefs of the Assyrian Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal, most of them are at the British Museum, but they are Mesopotamian, today’s Iraq.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections, and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.