Art News

The Boy in the Fur: An Interview with Tracy Kerdman

The Boy in the Fur: An Interview with Tracy Kerdman

Step into the uncanny valley with New York-based artist Tracy Kerdman. Outwardly concerned with what might be deemed creepy, surreal, or unsettling, her work explores deeper concepts permeating culture and an examination thereof. Kerdman’s work recalls concepts put forward by Twentieth century philosopher Jean Baudrillard, who discussed postmodern society’s inability to distinguish between reality and a close copy, a simulacrum. Almost all of her subjects are depictions of what looks like life—characters comprised of combinations from real life and imagination, or sex dolls, whether recognizable or reduced to a single key part—with each blurring any sense of what was real in the first place. Art imitates life and life imitates a model.

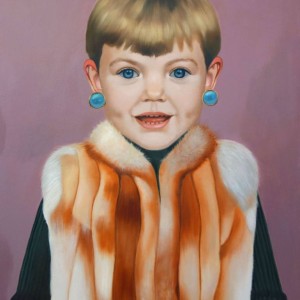

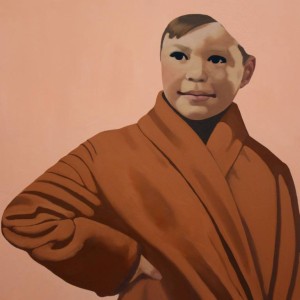

In particular, her plasticine-like portraits depicting young gender-bending boys explore what gender means as an collective conscious, questioning a long-standing binary. This exercise is meant to elicit an emotional response in viewers that turns back on itself in recognition of what it means to have an ingrained notion of masculinity and femininity. An increased examination of this disparity is ever-resonate today as a heightened social awareness of gender construction incubates. Color authority Pantone chose a pink and blue hue respectively for their colors of the year, a clear nod to the topicality of this conversation. Tracy Kerdman has titled this series of portraits People of Faux, culling pieces from real life to manufacture her own conception of what a more fluid adoption of prescribed norms might look like.

Read below to learn more about how Tracy creates her People of Faux and what they mean to her.

What sort of political/social platitudes do you intend to comment upon with this series?

I wasn’t necessarily looking to make a particular statement with these paintings, but rather to call attention to the general idea of gender and what exactly that means, to give those feelings a face. So while there is no one criticism of gender, the idea of it as it stands socially and currently in our culture is examined. Often this idea manifested itself in young boys portrayed in an assumed feminine way. Sometimes the results rendered were disturbing or amusing. I often wonder if the reverse had been executed, a girl portrayed in a so-called masculine way, if the series would be about a different topic altogether.

What’s the significance of employing youth as the vehicles of this message?

Sometimes children have the ability to blur the lines between male and female. Some young boys’ features can effortlessly translate into the looks of a young girl, which makes an interesting subject for a portrait. I like to show the closeness of genders before they are so starkly separated. In the West during the mid-16th to early 20th century, it was commonplace for boys between the ages of two and eight to wear dresses. This was known as being “unbreeched.” At these young ages, there was little to no differentiation between the sexes. It was a matter of practicality. Now, the matter of gender distinction seems to begin right at birth, if not before.

You’ve stated you draw inspiration for the portraits from vintage, black and white photographs. What sort of common lines do you draw between the photographs to then combine them into one image?

To be straightforward, I never really know the common lines until I put it on a canvas and start painting. There is a lot of trial and error involved. I would usually begin with an idea I was excited about and that I hoped would make for a good painting. Unfortunately, more often than not there are no connections between the images, and I am left with an idea that doesn’t work out. I often paint out a head just to replace it with another in order to revive the work and call it a day.

When I first started this method of combining multiple images into one, I made a lot of awkward work. It took me awhile to know what would typically make a decent painting. Looking back now it’s easier to recognize what a bad combination looks like, and whether it has the ability to make sense visually. For every one good connection there are ten that have failed. Some things just do not translate no matter how hard you try.

By recalling the past, what do you wish to say about the future?

Context is imperative when making any kind of meaningful or thoughtful statement, especially in painting. I think that only in taking a step back to look at a subject as a whole can you even find something to say about the future. In these paintings, I hope to call attention to the culture of gender as a whole, and where values of male and female stand in society today. Hopefully for the future, the specific voice that is carried on from the work is individualistic and personal and will contribute to a greater narrative.

Each of the portraits has an endearing feel to them, while also touching on these deeper issues of gender. How important is the use of lightheartedness or humor to explore this?

The work is not intentionally humorous. The goal is a compelling image or face, or just trying to make an interesting portrait. Sometimes the only way to achieve that is by removing details from a face or choosing an image that may seem bizarre to begin with. When pursuing a painting in this series the important things were the particular lighting in a photograph, a person’s specific features, mannerisms, and dress. I believe creepiness and uneasiness can sometimes turn into humor and vice versa. Perhaps the subject of a boy portrayed in a softer way is inherently seen as humorous, which can be a topic all on its own.