Art News

Art in Motion: The Story Behind Mobiles

Most people are familiar with baby mobiles. Fewer know them as an interior decorating accessory. And even fewer know them as a fine-art form. What are mobiles? Who invented them? To start, mobiles are a type of suspended sculpture based on balance and characterized by the ability to move. They range in size from a few inches to more than 100 feet and can cost anywhere from $10 to almost $26 million.

(Image: Courtesy of Houzz)

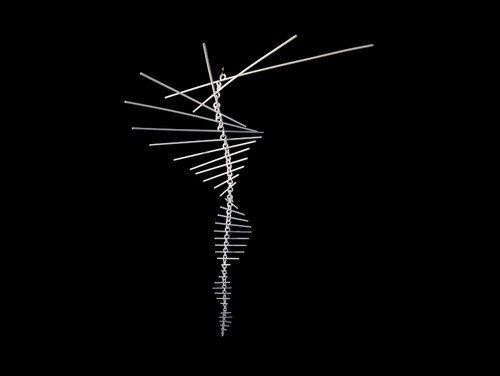

Shown: A large custom mobile I made for a client in Buenos Aires, Argentina. He requested a design strongly influenced by Alexander Calder’s work. It’s shown here at a park in Richmond, Virginia.

(Image: Photo by Toni Knuutila, Courtesy of Houzz)

The History of Mobiles

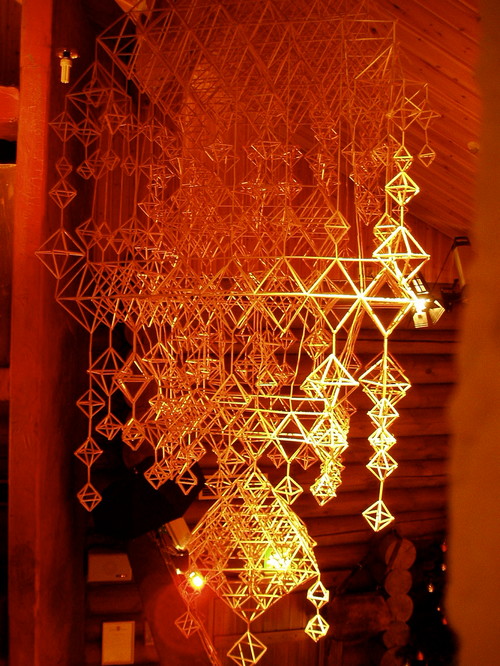

Mobiles have existed in the form of wind chimes for thousands of years. People in Greece, Rome and Asia made them with bronze or glass, often with bells attached, and hung them outdoors for good luck or to ward off evil spirits. In Finland people made (and still make) traditional hanging sculptures out of straw called himmelis, from the Germanic “himmeli” meaning “sky” or “heaven.” Usually pyramid shaped, they were traditionally placed above the dining table to ensure a good crop for the coming year.

However, mobiles as an art form didn’t really start to exist until the early 20th century, when the Russian artists and early kinetic sculptors Aleksander Rodchenko, Naum Gabo, and Vladimir Tatlin began to experiment with it.

The first real breakthrough came in 1920, when the American artist Man Ray assembled 29 coat hangers based on the whippletree, a mechanism that has been used for centuries to distribute force evenly through linkages when horses or mules pull a plow or a wagon. (If you’d like to see an example of a whippletree, look at your windshield wipers the next time you get into your car; they’re based on the same mechanism and contain the same structure as a basic mobile). He called his piece “Obstruction,” and it is the first of this type of hanging kinetic sculpture. Man Ray also experimented with hanging abstract pieces of sheet metal.

In the late 1920s, Bruno Munari, an Italian artist, designer, and inventor, started to make what he called “Useless Machines,” pieces of art that could interact with their environment. A number of them resemble what would become modern art mobiles.

Shown: A traditional Finnish himmeli

(Image: Photo by Jeff King & Company, Courtesy of Houzz)

Alexander Calder and the Birth of Modern Mobiles

The next and biggest breakthrough came in the early 1930s, when American sculptor and trained mechanical engineer Alexander Calder started to apply the whippletree mechanism in a new way. Instead of attaching lower elements to both ends of the wires, he replaced one on each arm with an abstract shape. This opened up a new universe of possibilities, and Calder explored it without hesitation, making thousands of awe-inspiring mobiles over the next four and a half decades, ranging from miniature sized to 100 feet.

Albert Einstein, upon seeing the 1943 Calder exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, lamented: “I wish I had thought of that.” In a way Calder (or just “Sandy,” as many who are familiar with him and his work call him) invented a new art form, which can be said of very few artists. He broke through the limitations of what sculptures can be.

The term “mobile,” a French pun meaning both “mobile” and “motive,” was coined by Marcel Duchamp while visiting Calder’s studio in 1931 — although he apparently had already used the term in 1913 for his “Bicycle Wheel,” which some consider to be the first kinetic sculpture.

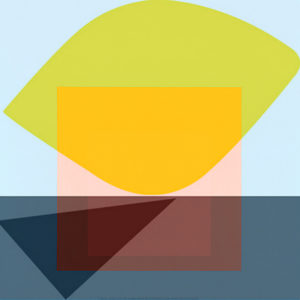

Shown: An Alexander Calder-inspired mobile in a San Francisco kitchen

More Metal Art Options for the Home

(Image: Photo by David Stark Wilson, Design by WA Design Architects, Courtesy of Houzz)

Calder’s work (along with mobiles in general) has recently received renewed attention and interest, partly due to a recent show of it (designed by architect Frank O. Gehry) at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

The Calder Foundation, founded and run by his grandson Alexander S.C. Rower, has been brilliantly managing Calder’s body of work. Several recent auctions of some of Calder’s best mobiles were highly successful and included pieces such as Snow Flurry, Lily of Force, and Poisson volant (Flying Fish) — the latter of which sold for $25.9 million, the most paid for one of the artist’s works.

This month’s Art Basel in Miami Beach featured a number of works by Calder. Reporting on the world-renowned art fair, The Art Newspaper stated: “Among the works by the hundreds of artists brought by 267 galleries from 31 countries, mobiles definitely constitute a trend.”

Shown: A Calder-inspired mobile in a home entry in Berkeley, California

Home Interiors Enhanced by Mobiles and Other Art

(Image: Photo by Marco Mahler, Courtesy of Houzz)

Mobiles Today

Mobiles remain a much-uncharted art form. Not many sculptors have fully applied themselves to the form yet, probably partially due to Calder’s dominance of the genre. Art critic and Los Angeles Times contributor David Pagel refers to mobiles as, “a genre of sculpture [Calder] may not have invented but owns so completely that it’s almost impossible for another artist to make a mobile and not be compared, unfavorably, to Calder.” As someone who makes mobiles professionally and prides himself on his creativity and the quality of his work, I would like to make sure you noted the word “almost” in that sentence.

Over time mobiles have slowly evolved from their early midcentury modern style to a variety of contemporary designs in a range of materials, and many possibilities and styles remain unexplored. Essentially, they can be customized to any style and space: contemporary, modern, traditional, industrial, or rustic; small, large, wide, narrow, or flat. And mobiles don’t compete with other objects, since they are up and above in mostly unused real estate. I see spaces that could use a mobile almost everywhere I go.

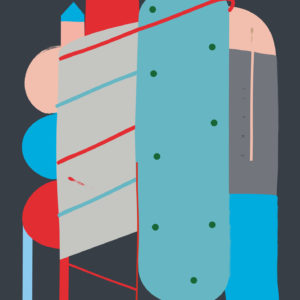

Shown: Two out of a series of three mobiles I designed and made for the atrium at a hotel in Northern Virginia. The design was inspired by the architecture of the Butterfield House in New York City.

(Image: Photo by Marco Mahler, Courtesy of Houzz)

Fourteen years ago I visited the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and came across Calder’s mobiles for the first time, including the 76-foot-long mobile in the East Building (a must-see for anyone visiting the city, in my opinion). Shortly after that, I made my first mobile for my baby nephew. It looked quite strange, made of wire, cork, and aluminum foil (I was thinking the shimmering foil would capture a baby’s attention); definitely not your conventional baby mobile. I very much enjoyed making it, and I kept experimenting with minimalistic wire mobiles.

Eventually, someone asked me to make a larger custom mobile for a restaurant. Then I got another request to make custom mobiles for New York Fashion Week, and gradually what had started as a hobby turned into a full-time profession. Since then I’ve made a wide variety of retail mobiles, large custom mobiles, 3D printed mobiles (apparently the first ones in the world) and standing kinetic sculptures.

Shown: One of a series of 3D printed mobiles that I designed with Henry Segerman, assistant professor in the Department of Mathematics at Oklahoma State University. With the balance points calculated to 1/25,000th of an inch, it comes out of the printer completely assembled.

The longer I make mobiles, the more I love making them, maybe because I get better and better at it. Mobiles add another dimension to a design. Besides materials, shapes and colors, they also involve motion, which makes them especially fascinating to me. I like the additional challenge and the possibilities that come with the motion. Mobiles interact with their environment through air currents or touch, which can make them sometimes appear to be almost alive. Mobiles are a young art form, and I like working in a field that still has a lot of uncharted territory. And I love the way it feels to look up at a large-scale mobile.

(Image: Photo by Marco Mahler, Courtesy of Houzz)

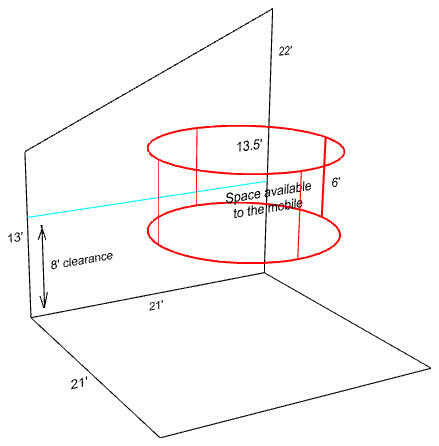

Three-dimensional modeling software allows for precise planning and designing as well as clearly illustrating different options to the client.

(Image: Photo by Marco Mahler, Courtesy of Houzz)

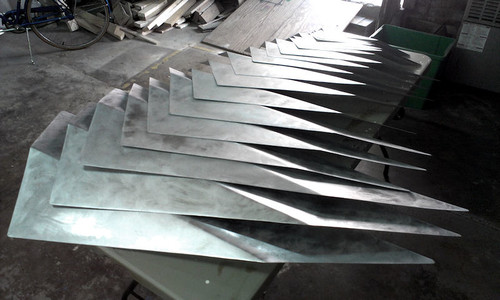

These are large unpainted sheet metal pieces at my workspace, ready to be assembled into a mobile.

(Image: Photo by Marco Mahler, Courtesy of Houzz)

To finish, here is one of my favorite Alexander Calder quotes, talking about his mobiles: “This is completely useless and meaningless. It’s just beautiful, that’s all. It can make you very emotional if you understand it. Of course, if it had some meaning it would be easier to understand, but it’s too late for that.”

Shown: One of my original mobile designs, and one of my favorites.