Art News

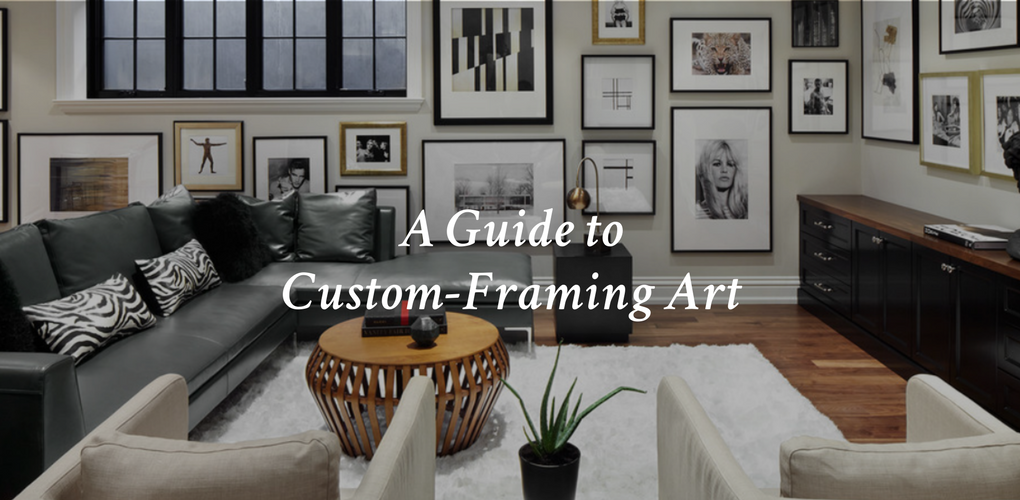

A Guide to Custom-Framing Art

Need to custom-frame some artwork but feel overwhelmed by all the choices? You’re not alone. Aside from the different colors and finishes, you’ve got to consider scale, the design of the piece and whether to use a mat or two — or three. Conservation, acidity, and UV- and infrared-blocking capabilities come into the mix too. This guide can get you in the right frame of mind to make educated choices.

(Image: Photo by Toby Scott, Design by Claire Stevens Interior Design, Courtesy of Houzz)

Browse Frames by Size, Shape and Style

Mats

Similar to how hair bangs can frame a face and highlight facial features, a mat helps highlight artwork by separating it from the frame and drawing attention to the artwork.

A mat isn’t necessary, but most artworks on paper—such as photographs, drawings and watercolors—look best when there’s a border between the edge of the artwork and the frame. After all, making your piece look its best is one of the goals of framing in the first place. The piece shown here wouldn’t look nearly as elegant and finished if it were framed without the mat. It would probably read as too poster-ish.

Besides highlighting the artwork, a mat also physically distances and prevents the artwork from sticking to the glass.

(Image: Photo by Striving Artists Framing and Art Services, Courtesy of Houzz)

Paper mats. Paper mats can be acidic or non-acidic. Acidic paper mats, sometimes called “decorative mats,” are made with wood pulp. An acidic compound in the wood pulp called lignin creates yellow and brown burn marks on the artwork. One way to tell if a piece has been framed with an acidic mat is if the bevel has yellowed over time. If it’s acid-free, it should still be white.

It’s generally OK to use an acidic mat on inexpensive, easily replaceable pieces, like posters. However, if you’ve purchased pre-matted artwork or have a piece that was matted a long time ago and you aren’t sure what type of matting was used, it might be worth replacing it with a non-acidic mat to be safe. Decorative mats are the least expensive mats available, and some framers don’t even carry them because the cost difference between them and acid-free mats is negligible.

Regular mat board (also called paperboard). Regular mat board is still made of wood pulp, but it’s been acid-neutralized. This is the most commonly used mat material and is advertised as “acid-free.” It should last about a hundred years or so. Acid mat board does cost more than regular (acidic) paper mats, but not much more. This type of matting is best for most pieces, like low- to mid-range artwork and photos.

One hundred percent cotton rag mats (also known as rag mats). These are constructed of a cotton rag core and backing paper, which rests near the artwork. Rag mats are acid-free and high-quality for most works of art. Like regular mat board, this type of matting is also appropriate for artwork that doesn’t need a high degree of conservation. Rag mats can be used for anything from cherished family photos to watercolor paintings.

Conservation or archival mat board. This is the most expensive, least acidic material. It’s made of pH-neutral cellulose that’s been treated to be inert for hundreds of years and is used on more valuable pieces and works that require the highest level of preservation.

Other mat materials include vellum, suede and fabric-wrapped mats, such as linen. The green mats shown above are fabric-wrapped.

(Image: Photo by Bertolini Architects, Courtesy of Houzz)

Mat scale. Boris Smorodinsky of Striving Artists Framing and Art Services in Los Angeles says there’s no hard-and-fast rule as to how wide a mat should be in relation to the artwork. In fact, framing in general is subjective and depends on the piece and the client’s personal preferences. However, Smorodinsky usually starts with a minimum width of 2 inches.

Multiple mats. The addition of a second mat or even two more mats creates a more pronounced visual delineation that helps draw the viewer’s eye to the artwork. However, Custer follows a rule: “Never let the presentation overwhelm what is being presented, meaning the framing is there to make the artwork look its best, not the other way around.” So more isn’t always better.

Colored mats. Adding a color-contrasting mat can accentuate the artwork even more. Whether to introduce a colored mat, however, is a personal preference. Suzanne Gallagher of Wall Design Diva in Portland, Oregon, says the wrong-color mat can be the “death of an image.” She recommends using a neutral mat for the dominant border (white is classic these days), and adding a colored secondary mat that references a color in the artwork — but only if it truly enhances the image.

(Image: Photo by Lesley Unruh, Design by Barker Freeman Design Office Architects Pllc, Courtesy of Houzz)

Frames

As with mats, frame choices are numerous, and choosing the right frame for a piece is a personal decision. Frames are made of a variety of materials, like wood, metal, resin, and gesso and gold or silver leaf.

Frame cost. Thin frames made of resin (polystyrene) are the least expensive at around $5 per lineal foot; highly decorative wood frames can cost as much as $100 per lineal foot, but the average frame runs in the range of $15 to $25, Smorodinsky says.

Standard frame molding comes in pieces 118 inches long. However, it is possible to frame an extremely large piece.

Since selecting a frame can be overpowering for many people, Smorodinsky likes to streamline the process for his clients. Before they arrive, he asks his customers to take a few photos of the room in which the piece will be hung, measure the room dimensions and bring a swatch of the wall color. “We ask a lot of questions to understand our customer’s living space,” he says. “It’s important that the finished piece doesn’t fight with its surroundings.”

Custer recommends first letting your framer know what your budget is so he or she can show you designs appropriate for the amount you want to spend. That way nobody wastes time, and you don’t fall in love with something you can’t afford. He also says to not be shy about asking questions or expressing your likes and dislikes.

(Image: Photo by Lisa Petrole Photography, Design by The Design Co., Courtesy of Houzz)

Frame Guidelines

While frame selection criteria is fluid, framing professionals agree on two rules of thumb.

1. The frame width should be skinnier than the mat. Custer says a 1-inch-wide frame would look strange with a 1-inch-wide mat. It’s best to have a larger mat to create a variance in width.

2. Select the best frame for the piece instead of matching another frame. This tenet is true for diverse artworks on a wall, like a mixture of photographs, drawings and paintings, not a collection of similar works. “Nine times out of 10, if you do what’s best for the art, it will look great in the room,” Custer says.

Sometimes a client will come to him with a photo of another frame or other finishes in the room and want the new frame to match. The danger in this is if he tries to match something and it falls a little short, it won’t look right. The best approach is to find something complementary to the finishes in the room that will still work with the art.

The installation shown here pretty much hits on both points.

Frame Trends

Frame trends don’t pass as quickly as clothing and makeup trends. Framing can be pricey, so you want your investment to last and look good for a long time. However, there are a couple of framing trends of which you should be aware.

Custer says white frames are particularly hot right now, especially with contemporary art. “White is the new black,” he says.

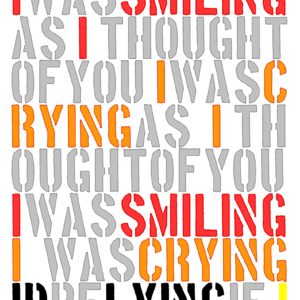

Another trend he points to is pairing very modern works of art — even graffiti-style pieces — with classic, ornate frames.

Shadow boxes. Shadow boxes house mounted 3-D objects within a deep frame. “Shadow box framing is all about problem solving,” Custer says. Mounting an object in a frame is about figuring out what will work best while being the least invasive to the object. Sometimes, the object is hand-stitched to a mat board or recessed into the mat, or small shelves or supports are created to suspend the object.

The key is to always make the mounting the least visible and reversible, so permanent materials like staples or glue aren’t used in shadow boxes.

(Image: Photo by Shawn Talbot, Design by Begrand Fast Design Inc., Courtesy of Houzz)

Going frameless. Paintings on a canvas stretched over wood stretcher bars can be framed or unframed. These are usually oil or acrylic paintings. If you leave a painting unframed, you’ll see the side of it, which is typically gesso white or the color of the raw canvas or linen.

Here, the two paintings on the right are unframed, while the larger painting on the left sports a slim stained wood “floater” frame, which has a gap between the painting’s edge and the inside edge of the frame.

(Image: Photo by Adrienne DeRosa, Courtesy of Houzz)

Unframed paintings have a sense of casualness that can be quite charming, like in this installation. However, you need to be OK with possibly seeing some smears of paint on the edge and the thick bump created by the canvas folded over at the corners.

Another frameless option is a giclée (pronounced zhee-KLAY) print. It’s a type of inkjet print that uses fade-resistant, pigment-based archival ink that can be printed onto canvas, among other materials. Unlike with a regular painting, the image wraps around the sides.

(Image: Photo by Maxwell & Company Architects, Courtesy of Houzz)

Fill Your Gallery With Contemporary Furniture

Glass

Do you know when to use museum glass, regular glass or Plexiglas, or even when to use glass at all? Either glass or Plexiglass is used to cover paper-based artwork and protect it. Oil and acrylic paintings should be left uncovered because they release gases as they cure and need to breathe. Glass is also heavy and can be an obstacle for large pieces or ones that need to be shipped.

To choose the appropriate option, Gallagher of Wall Design Diva recommends considering the value of the art, budget, installation location and desired design effect. Your framer can guide you in the right direction. Here are the options and their characteristics:

Regular plate glass:

○ Highly reflective

○ Doesn’t block any UV rays

○ Least expensive option

Conservation clear glass:

○ Reflective

○ Blocks 99 percent of UV rays

○ Costlier than regular glass but less pricey than museum glass

Museum glass:

○ Nonreflective

○ Blocks 99 percent of UV rays

○ Most expensive glass option

No glass can protect 100 percent against UV rays. The best preventive measure is to also install a UV-filtering film on your windows. Even if only 1 percent of UV rays gets through, it can affect the artwork over time.

Plexiglas. Plexiglas is an option for large pieces or artwork that needs to be shipped because, being made of acrylic, it’s much more lightweight than glass. Like glass, it’s available in regular and UV-filtering options.

Custer points out another benefit of Plexiglas over glass. “It’s not just UV rays that can harm your art,” he says. “The infrared light spectrum can be just as damaging. It can effectively cook pigment and paper and cause just as much damage, especially if the work is under glass. Glass is an excellent conductor of heat and can intensify the damaging aspects of infrared light. Plexiglas, on the other hand, is an insulator and can actually reduce the possibility of [infrared] damage.”

Optimum Museum acrylic, made by Tru Vue, is an acrylic with added UV-filtering benefits, and it’s antireflective and scratch-resistant. Costing more than museum glass, Optimum Museum Acrylic is the most expensive option. Conservation Clear acrylic, also made by Tru Vue, is another option with the same UV benefits, but it’s reflective.

Whatever options you decide on with your framer, make sure he or she is a member of the Professional Picture Framers Association. Not only are members seasoned pros at framing, they are constantly learning about new materials and techniques.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.