Art History 101

The Evolution of Street Art

With the benefit of hindsight, we can easily categorize the likes of Impressionism or Abstract Expressionism, but defining an art historical movement as it develops in real time is a more difficult, albeit exciting, endeavor.

Today we are witnessing the growth of Street Art, a movement so new and contentious that calling it a movement at all sparks controversy. The term Street Art, also known as Urban Art, encompasses a number of disparate practices—public murals, spray paint on canvas, and even manufactured consumer goods. With scrappy beginnings well beyond the influence of white cube galleries—and the confines of the law—Street Art has become one of the most popular, cohesive, and commercially successful art movements to emerge out of the postmodern milieu.

Origins

Accessibility was at the crux of Street Art in its most nascent form, graffitiing and tagging public spaces with the artist’s moniker or symbol. The practice allowed underrepresented, often impoverished young people to make their voices heard with just a can of spray paint and some grit—no studio or gallery representation needed.

In 1970s America, graffiti writing proliferated major cities. Tagging emerged as a form of self-expression for young people who were far removed from the art world and often alienated from society in general. Darryl McCray, better known through his graffiti by his nickname “Cornbread,” for instance, was in juvenile detention by the age of 12, where he passed his time discreetly covering the walls with his signature. After his release, he took to tagging the streets of Philadelphia, at one time using the medium to declare his love to a crush (“Cornbread loves Cynthia”) and once to disprove a newspaper report that he had been killed in a gang shooting (“Cornbread Lives”).

As city officials sought to crack down on the guerrilla art form, graffiti writers met the challenge, trading their simple tags and hurried signatures for more complex, virtuosic lettering in bold colors and shapes. With this new brand, dubbed “wildstyle,” graffiti writers upped the ante: they were already engaging in a high risk practice—vandalizing public spaces—and the riskier the location, the greater the prestige. The complex, interlocking letters typical of the wildstyle motif made the act all the more difficult and all the more impressive among street art circles.

The transition from graffiti writing to graffiti art can be pinpointed to the development of wildstyle, which coincided with the commercialization of graffiti and its assimilation into the art world. Artist Tracy 168, a pioneer of wildstyle graffiti who first took to the streets in 1969, saw his works embraced by the art world and eventually exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, one of the most famous American artists of the twentieth century and a protege of Tracy 168, catapulted the movement into the galleries. Basquiat began graffitiing as a teenager in New York in the 1970s, tagging the streets with his own anti-establishment credo, “SAMO” (short for “Same Old Shit”), which he sought to make as ubiquitous as the Pepsi logo.

Basquiat took his street art motifs to the canvas and was swiftly embraced by the art world for his confluence of collage, graffiti, comic book motifs, mythological themes, and accessible narratives. By 1983 he had been included in the Whitney’s Biennial exhibition and two solo shows at Gagosian.

Influence of Propaganda

Inspired by the rabble-rousing graffiti igniting the New York streets and art scene, French street artist Blek le Rat began spray-painting stencils of rats around the streets of Paris in 1981, with “rat” as an anagram of “art” and a symbol of the plague-like proliferation of art into public spaces that he sought to achieve. Blek le Rat also drew inspiration from another thread in the history of street art—World War II political propaganda, particularly stencils across European city streets of the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini.

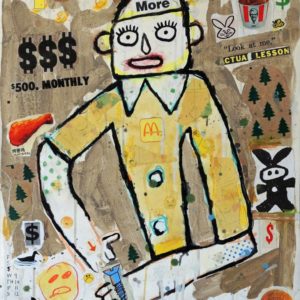

The graphic style of street artist Shepard Fairey can also be traced to propaganda—early in his career, Fairey tagged streets with stickers bearing an ominous face and the word “Obey.” He then took the motif to murals, posters, and a host of merchandise under his fashion label OBEY Clothing. In practice, Fairey’s enterprise is wildly commercially successful—the dissemination of the logo generates intrigue and spurs viewers to participate by purchasing and wearing the logo. This commercial success, however, also reifies Fairey’s conceptual goals—to explore the proliferation of advertising, the way viewers assign meaning to signs and phenomena, and the power of conspicuous consumption.

Commercialization

Though many contemporary artists decry commercialization, street artists have long used consumer goods as a means to both capitalize on their work and make it accessible to broad audiences outside of the gallery space.

While Basquiat sold sweatshirts and postcards bearing images of his work, his contemporary Keith Haring opened his own store, Pop Shop, in downtown Manhattan in 1986. Through Pop Shop, Haring offered low cost versions of his work—t-shirts, buttons, and posters—to an expanded audience that might not otherwise participate in the art world. Retail became a crucial way for Haring to reach the public alongside his murals and posters. As the artist said of his Street Art practice, “This was the first time I realized how many people could enjoy art if they were given the chance. These were not the people I saw in the museums or in the galleries but a cross-section of humanity that cut across all boundaries.”

A Movement in the Making

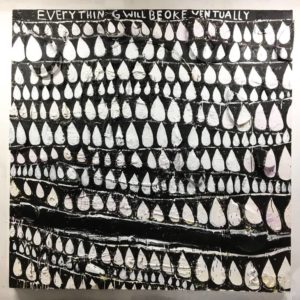

Like its predecessor Pop Art, Street Art borrows the visual language of mass culture to generate works of art that are accessible to and resonate with broad audiences—a virtue that has resulted in its commercial boom. In 2011, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles curated “Art in the Street,” which set MOCA’s record for most-attended exhibition in the museum’s history. Just this year, a piece by internationally renowned street artist Bansky sold for $12.1 million at auction.

Though many are uneasy with the art world’s infatuation with the historically anarchist movement, street artists continue to use public space and consumer goods with the aim of accessibility. As Blek le Rat has explained, “Urban Art is there to be inclusive. By bringing our work to the masses within the urban landscape, on the streets, we are including everyone.”

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections, and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.