Art History 101

Happy Birthday, Hannah Höch

Today we celebrate the birthday of Hannah Höch, the sole female member of the Berlin Dada group—the short-lived but influential German iteration of the Dadaist “anti-art” movement—whose pioneering contributions to the collage medium and postmodern art in general went largely unsung throughout the twentieth century.

Famously (and regretfully), there was no mention of Hannah Höch in Robert Motherwell’s 1951 survey Dada Painters and Poets. And despite being self-proclaimed feminists, her own dadaist colleagues opposed her inclusion in the First International Dada Fair in Berlin in 1920—at least until her romantic partner and fellow dadaist, Raoul Hausmann, threatened to drop out if they excluded her. Looking back on the modernist art scene in Germany, Höch recalled, “They continued for a long time to look on us women artists as charming and gifted amateurs, denying us any real professional status.” Even on the occasion of her death in 1978, a newspaper headline referred to the late artist as “the bob-haired muse of the men’s club.” In the face of such marginalization and sexism, Höch made great strides to politicize the collage medium, critique gender expectations, and incisively capture the freneticism and uncertainty that shook German society during the tumultuous interwar period.

Born November 1, 1889, in the Central German town of Gotha, Höch’s education at the School of Applied Arts in Berlin spanned glasswork, painting, and graphic design. Though she trained and worked in a number of mediums, she is most famous for her photomontages, which cheekily commented on mass media and popular culture during the Weimar Republic, the failed representative democracy that briefly governed Germany between World War I and the rise of the Nazi party.

Höch likely cut her teeth collaging from 1916 to 1926 at the publisher Ullstein, where she designed embroidery and lace guides for periodicals such as Die Dame and Die Praktische Berlinerin, magazines geared toward bourgeois women. Höch’s work there doubtlessly informed her artistic elevation of women’s work and her conceptual focus on gender issues, a concern that was singular within her male-dominated Dada group.

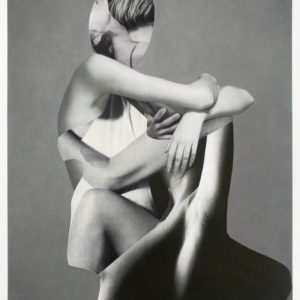

Höch pulled many of her images from women’s magazines to explore the Weimar ideal of the “New Woman”—the archetype of a modern female newly liberated by the right to vote, progressive views on sexuality, and increased financial independence. Höch’s collages exposed the gap between the ideal and the socioeconomic reality of women, astutely contemplating the progressive rhetoric surrounding gender versus the still patriarchally-entrenched social practices of the day (practices to which even the radical Dadaists were not immune). In “The Beautiful Girl” (1920), for instance, a curvaceous female body foregrounds BMW logos and symbols of industry, pointing to women’s increased mobility in the job market—a development that promised equality but beget sexism and harsh working conditions. The oversized, bouffant hairdo that occupies the left of the picture plane cartoonishly looms above the central figure, a parallel to the standards of femininity that persisted even as women enter the labor force alongside men.

But Höch’s work was not limited to her female identity—she also captured the ennui and ambivalence that struck Germans of all stripes, particularly in the face of rapid industrialization. Her famous Dada Dolls, cyborgian animal-human hybrids, explore the unease surrounding technology’s proliferation into daily life. In contrast to her fellow dadaists, who treated art primarily as a vehicle for discourse rather than an aesthetic end unto itself, Höch’s formal training persisted in her collage practice. Her 1923 collage “High Finance,” which depicts a banker’s head cleaved in half by a shotgun, jabs at the relationship between the military, industrial power, and capitalist accumulation, while also maintaining a dynamic composition of intersecting planes and opposing forms.

Höch was as singular in her life as in her art: after splitting ties with the Berlin Dadaists in 1926, Höch relocated to the Netherlands, where she worked closely with Bauhaus artists and began what would become a decade-long romantic relationship with a woman, avant-garde writer Til Brugman. During World War II, while many artists scattered or were forced to flee, Höch quietly isolated herself in the suburbs of Berlin, where she continued her work (despite being branded a “degenerate” artist by the Nazi party). Höch’s dizzying, exacting photomontages set the precedent for many collage artists working today, and she has even been credited with inspiring the bricolage punk aesthetic that emerged in the 1970s. As the only woman in the Berlin Dada group, the most political iteration of Dada, Höch developed a radical visual language that continues to speak to us today.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections, and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.