Art History 101

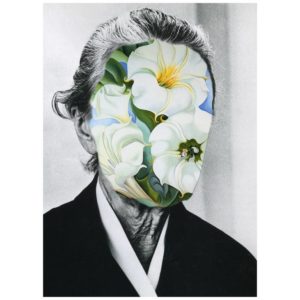

Georgia O’Keeffe, An American Pioneer

Georgia O’Keeffe captivated audiences with her peculiar approach to abstraction and mystified critics with her radical attitude towards artistic and gender expectations. At a time when American women were fighting for suffrage and female artists were patronized as little more than hobbyists, O’Keeffe weathered reductive, often sexist criticism to invent a distinctly American form of modernism.

The pulsating colors of her sweeping flower petals preceded American color field painters Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, and her bleached animal bones captured a transcendent vision of both the American landscape and the potential for abstraction. But those aesthetic achievements did not come easily, nor were her feats readily acknowledged by the art world. Born November 15, 1887, O’Keeffe trained at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Art Students League in New York, where she learned the techniques of realist painting under William Merritt Chase. However, inspired by painter Arthur Wesley Dow’s aim to capture nature’s essence rather than a faithful representation, O’Keeffe began to explore pure abstraction—becoming one of the first American artists to do so.

In 1915, an early set of O’Keeffe’s abstract charcoal drawings were shared through a friend with photographer and owner of the avant-garde 291 Gallery Alfred Stieglitz, who upon seeing the drawings allegedly declared, “At last, woman on paper.” The exchange sparked Stieglitz and O’Keeffe’s tumultuous relationship as dealer and artist, photographer and muse, and husband and wife. Stieglitz’ remark would also precede the sexual interpretations that came to dominate criticism of O’Keeffe’s work, despite her protests.

On her status as a woman artist, O’Keeffe once declared, “I can’t live where I want to—I can’t go where I want to—I can’t even say what I want to. . . I found that I could say things with colors and shapes that I couldn’t say in any other way—things that I had no words for.”

From this frustration emerged a visual language for thoughts and experiences previously inarticulable. O’Keeffe’s floral and organic forms recalled the quietude and isolation of interior spaces—both mental and physical—but their homology with female anatomy was quickly taken up by male audiences for its pornographic potential, or read as a privileged glimpse into the feminine mystique. As a result, O’Keeffe was paradoxically pigeonholed by critics as maternal, childlike, or seductive. Stieglitz—whose radical nude photographs of O’Keeffe set the precedent for sexual associations with her work—alternately described her as “the Great Child pouring out some of her Woman self on paper, purely, truly, unspoiled.”

Later in her career, despite Stieglitz’ marketing of her work as such, O’Keeffe vehemently denied the gendered interpretations of her flowers. In a 1944 exhibition catalogue for her show An American Place, she cleared the air with exasperated finality: “You hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower—and I don’t.”

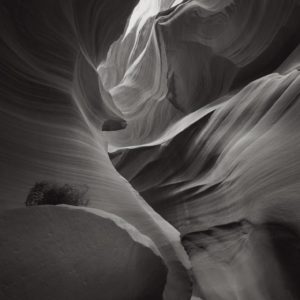

O’Keeffe’s daring oeuvre extends well beyond her storied flowers. While Stieglitz and his modernist circle worshipped Europe, O’Keeffe looked west to develop an American voice distinct from European abstraction. In 1929, she made her first sojourn to New Mexico, which she would regularly visit and finally make her permanent home in 1949. Back in New York, O’Keeffe painted cityscapes emphasizing the empty space between buildings—in New Mexico, expansive skies and sparse landscapes fueled her interest in negative space and offered ripe material through which she could explore the boundary between abstraction and representation.

O’Keeffe developed a consciously unconventional approach to abstraction in which she played with scale to push otherwise realist forms to the point of ambiguity. In her bleached bone series, for example, rather than altering the form of the bone itself, she magnified it to the point of abstraction, extending it to the edges of the picture plane. Her dizzying manipulation of scale was paired with rich, at times saccharine color palettes and flat brushstrokes to challenge our perceptions of space and surface.

Despite regular critiques of her work, O’Keeffe earned two major museum retrospectives in her lifetime, one at the Art Institute of Chicago and one at the Museum of Modern Art—the institution’s first retrospective of a female artist. Throughout O’Keeffe’s seven decade-long career, she defied expectations and boldly pursued her own form of abstraction to become a pioneer in American art.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections, and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.