Art History 101

From a Curator: Why I Love Roy Lichtenstein

My work isn’t about form. It’s about seeing. I’m excited about seeing things, and I’m interested in the way I think other people see things.

-Roy Lichtenstein

American painter, printmaker and sculptor Roy Lichtenstein (1923 – 1997) defined his hallmark style by hand painted commercially-printed Ben-Day dots (named after the illustrator and printer Benjamin Day). Why I love Roy Lichtenstein is because he often reinterpreted different styles across art history, parodying well-known paintings by old masters and transforming them into his own cartoonish creations. By satirizing accounts of art history, Lichtenstein simultaneously mocked the commodification of art masterpieces in advertising, printing, and other mass media.

In Bedroom at Arles, Lichtenstein alters the well-known painting of Vincent van Gogh’s bedroom (originally painted in 1888) and turns it into his own comic book scene. Using oil and magna (a paint made from ground pigment in an acrylic resin with solvents and plasticizer), he simplifies van Gogh’s original expressive swirls. Lichtenstein dramatically flattens the image of Van Gogh’s bedroom, morphing the floor into a simple patterned plane and the walls into panels of Ben-Day dots.

In Nonobjective II, most of the painting is pure Piet Mondrian, except for the areas we interpret as grey. Apparently the Dutch artist had not taken abstraction as far as it could go, because Lichtenstein takes it further: he abstracts the grey area into small spheres of color. To make the painting more confusing still, Non-Objective II isn’t an abstract but rather a representational recreation of a work by Mondrian.

Lichtenstein often acknowledged the “huge influence” that Pablo Picasso had on his artwork, even going so far as to paint cartoons of Picasso if only to free himself of the Spanish master’s influence. In many ways, Picasso inspired Lichtenstein’s tendency to re-use, borrow and alter the works of the past. As it happens, Picasso’s Les femmes d’Alger, painted in 1955 is actually a reinterpretation of the Romanticism painter, Eugène Delacroix’s Les femmes d’Alger (1834).

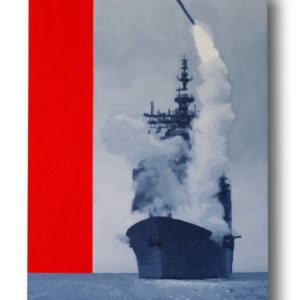

Originating in Italy in the early 20th century, Futurism aimed to capture the dynamics of speed, and glorify modern technology and war. The ideas of Futurism were eventually embraced by the fascist state under Benito Mussolini, and images such as Carlo Carra’s The Red Horseman (1913) became synonymous with the radical party’s political interests. Several decades later, Lichtenstein recreates The Red Horseman and embraces the Futurist idea of capturing movement and speed, but divests the image of its original political agenda.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections, and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Subscribe to Saatchi Art newsletters for your daily art brief.