Art History 101

Édouard Manet: The Father of Modern Art

Often cited as the father of Modern Art, Édouard Manet is a pivotal figure in the history of art. His quick, flat style of painting paved the way for the Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, and many other modern artists by rejecting the standards of the Academy.

Read on to learn why there would be no Monet if there had been no Manet…

Édouard Manet was born in Paris on January 23, 1832 to a wealthy and prestigious family. Though he developed a passion for art at a young age, Manet’s father intended for him to join the Naval Academy. After failing the entrance exam twice, his father reluctantly allowed Manet to pursue a career in art. He joined the studio of Thomas Couture, an academic painter, where he studied for six years. During this time he traveled to Germany, Holland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, and Italy studying and copying old masters of art.

Manet painted in an era in which the Academy still dictated what was acceptable and considered “good” art. Academic tradition valued classical technique and great paintings of great people and events, such as heroic scenes from history and mythological stories. Twice a year, the Academy hosted an exhibition known as the Salon, which was considered one of the most important exhibitions in Europe at the time. One of Manet’s earliest successes, The Spanish Singer, was accepted at the Salon in 1861 and earned him an honorable mention.

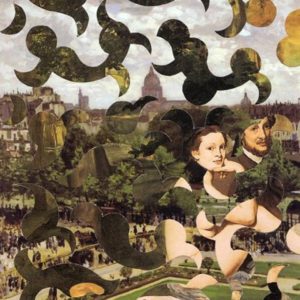

Though Manet aspired to have his work shown in the Salon, he agreed with other modern thinkers, like the poet Charles Baudelaire, that art should depict modern life, not historical events or mythological scenes. His friend and fellow artist, Gustave Courbet, stated, “Show me an angel, and I’ll paint one,” emphasizing his desire to paint the life he could observe around him. Manet’s modernist thinking can be observed in his 1863 painting Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe, or, Luncheon on the Grass, which was refused by the Salon. Instead it was shown at the Salon des Refuses, an exhibition of the large number of works rejected by the Salon that year.

Édouard Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, 1863. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

Luncheon on the Grass was heavily criticized by the academic community for its lack of accurate perspective and for the flatness of light and color. What the community hated the most was the unashamed and blatant nudity of the central figure – a prostitute – seated among recognizable gentleman figures, and staring directly at the viewer. This aggressive confrontation forced viewers to consider the less-than-savory realities of the modern world they were living in. Manet was offended by the reception his painting received. The painting has clear classical references, including Raimondi’s engraving of the Judgement of Paris and Titian’s The Pastoral Concert. However, Manet’s painting lacked the heroics and passivity of these classical works of art, and instead caused the viewer immense discomfort.

At the Salon in 1865, Manet caused another scandal with his painting, Olympia. Though Manet claimed to reference Titian’s highly-praised Venus of Urbino, viewers were offended yet again by the shameless and confrontational gaze of the female prostitute. While Titian’s Venus offered a guiltless object for the viewer to gaze upon, Manet’s Olympia forced viewers to acknowledge one of the more distasteful aspects of the modern Parisian lifestyle. In Manet’s words, “I paint what I see and not what others like to see.” The harsh lighting and sensual symbolism found in the painting further emphasized the abrasive message.

Though upset with the Academy’s rejections and criticisms of his work, Manet continued to submit his paintings to the Salon throughout the rest of his career, refusing to change his style to meet their tastes. Many paintings were rejected; some, including The Railway (1874), Argenteuil (1875), and Boating (1879) were accepted. Manet’s last great work, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, was shown in the Salon in 1882. Though accepted by the Salon, the piece was again criticized for its unsettling subject matter. Yet another depiction of modern Parisian life, the painting depicts not the life and joy of the popular music hall, but the weary and disconnected barmaid.

Manet’s firm disregard for the rules of the Academy inspired the coming generation of artists, including the Impressionists. The Impressionists also wanted to capture modern life, but unlike Manet, took their canvases outside and painted en plein air. Influenced by Manet’s flat use of color (which ignored the classical tradition of building layers), the Impressionists adopted a quick brushstroke in an effort to capture light. These artists, rejected by the Salon, began hosting their own exhibitions. Though Manet was invited to show with the Impressionists, he chose instead to continue to submit his work to the Salon, always working to change the expectations defined by the Academy.

Édouard Manet died in 1883 at the age of 51. Though his artistic career was relatively short, the legacy he left is great and vast. His refusal to conform to the ideals of the Academy, which had ruled for centuries, facilitated the rise of many modern artists who renounced classical tradition. Manet’s short career marks a significant turning point in the history of art, which explains why many consider him to be the father of modern art.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections, and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.