Art History 101

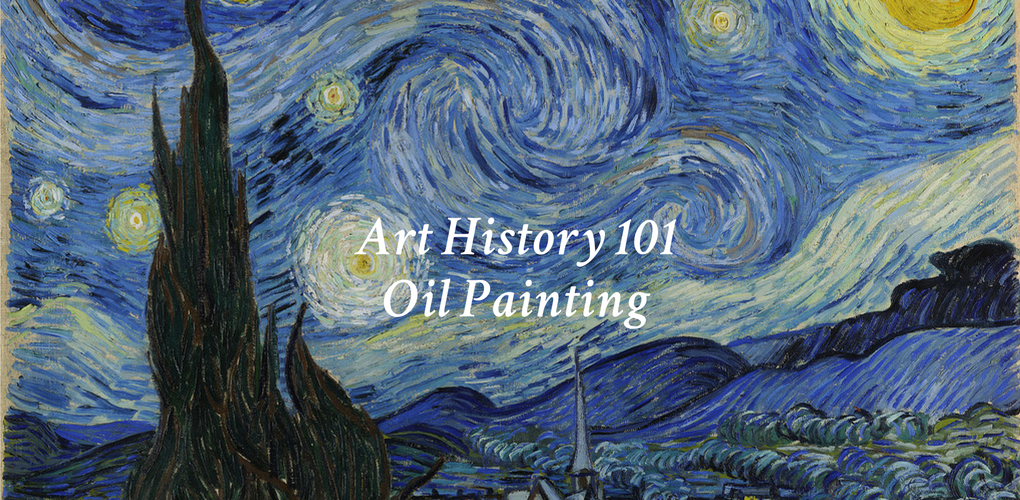

Art History 101: Oil Painting

Oil painting is perhaps the most dominant and popular art medium used in the history of art. The medium is lauded for its versatility, creating a range of opacity and intensity through infinite combinations of color and forms. Read on for a brief history of oil painting, and how different artists perfected this medium.

Brief History

The precise time when individuals began to use oil paint is unknown due to the impermanences of earlier oil paint recipes used in ancient times. Scientific research performed at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility shows that the earliest record of oil paint used in cave paintings from the Afghan region of Bamiyan dates back to the fourth and ninth century, almost a thousand years before Europeans started formulating oil paint recipes in the fourteenth century. Before pigments and materials became widely available through trade, people from ancient civilizations used protein based materials and animal fat as a binder, and extracted color pigments from a diverse source of plants and minerals.

Most early artists used tempera paint, which consisted of dry pigments, egg yolk, and egg white for paintings, murals, and frescos. As European artists continued to experiment with compositions and styles, eventually striving towards realism, they found the tempera formula too fast dying to manipulate the detail and precision they desired. Artists around the world began formulating oil paint recipes independently, using materials readily accessible in their region.

The use of oil paint as we know it is dated back to late fourteenth century Netherlandish painter Jan Van Eyck, who is cited by researchers as not the first to experiment with oil paint but the one who perfected the technique and medium.

In 1814, American portrait painter John G. Rand invented the first oil paint tube. With oil paint packaged and sealed in tin tubes to preserve its texture and consistency, artists were no longer confined to paint inside their studios, providing the possibility for en plain air painting. French Impressionist painter Pierre August Renoir accredited the Impressionist movement to this revolutionary invention, claiming, “Without paint in tubes there would have been…nothing of what the journalists were later to call Impressionists.” Many artists abandoned the traditional academic practices of working in studios based off studies and models. Painting in situ not only sparked spontaneity, artist were able to study and capture light and subjects with greater precision. (Source: Winsor & Newton)

Oil paint entered the phase of industrial-scale production by the nineteenth century. New and enhanced hues such as Cobalt Blue, Cadmium Yellow, Cerulean Blue, along with synthetic colors such as Zinc White and Ultramarine entered the market. The formulas have remained practically the same since. (Source: Encyclopedia of Fine Art)

Ingredients

The most basic components of oil paint include pigments in powder form, types of oils pressed from linseed, flaxseed or walnut, which function as a binder and drying agent. Pigments were not widely traded commodities during the renaissance; artists often extracted pigments from scratch and experimented with different recipes for optimal results. Analysis of paint samples from various historical paintings suggests regional preferences; whereas artists from northern Europe preferred to use linseed oil, those from the south, especially Italian artists, used walnut oil as binder and drying agent.

Beginning in the Medieval and through the Renaissance period, artists would grind minerals like Malachite for green, and Lapis Lazuli or Azurite for shades of blue. Modern discoveries of new chemical compounds and synthetic pigments provide artists with a wider range of colors and tones. Additives such as modified Alkyd resin binder are often added to enhance oil paint’s body, color retention, permanence, and drying time.

Read on to learn more about the different processes and techniques that artists used to create some of the most iconic oil paintings in history.

Jan Van Eyck – The Glazes

Born around 1390, Van Eyck was known for his sophisticated compositions full of iconography and context, meticulously executed with layers of paint as thin as one thousandth of an inch thick. With great control, Van Eyck layered glazes of almost translucent paint to create complex coats of colors that would shine through one another as light glares on the paint.

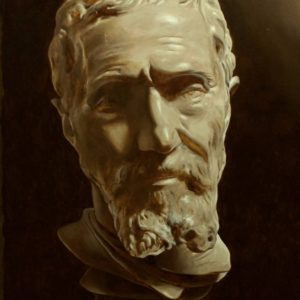

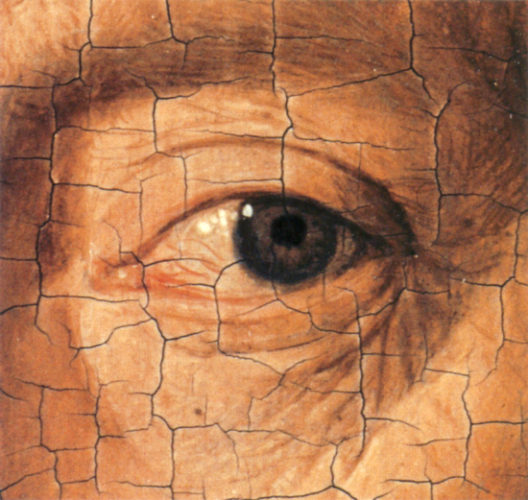

Leonardo da Vinci – The Sfumato

Leonardo Da Vinci is known as the Renaissance man who envisioned planes and tanks models centuries before their consummation. However, the technique behind Da Vinci’s immaculate paintings, Sfumato, is perhaps his greatest invention, which gave the world the transcendent Mona Lisa. Sfumato, (from Italian Sfumare, to “blend, fade, or evaporate in smoke) is the technique in which contours are delicately rendered with soft, seamless transitions, thus giving the sitters in Da Vinci’s portraits their youthful, exquisite grace.

The artist relentlessly studied the human anatomy in order to represent the figures as lively and realistically as possible. Leonardo Da Vinci painted tens, if not hundreds, of inconspicuous transitions to correctly contour and render one’s facial features. Da Vinci mixed almost undetectable amounts of pigment in oil, and slowly built colors with paint that is virtually translucent, which allowed the artist to compose the most subtle gradations.

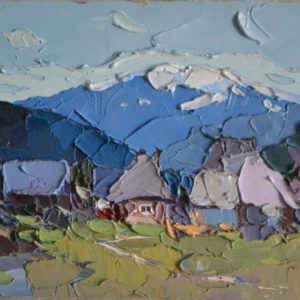

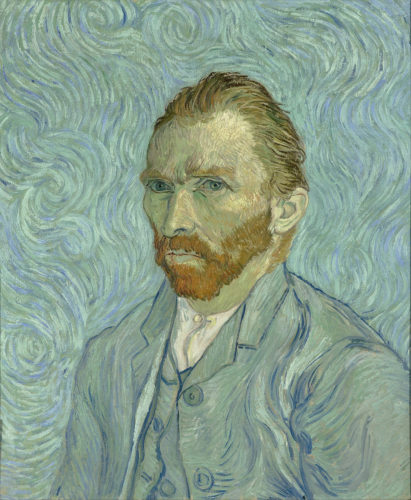

Vincent Van Gogh – Density

The Dutch Post-Impressionist only began to paint in the last ten years of his life. Tormented and plagued with depression and desperation after the Church’s rejection, Van Gogh painted profusely, producing over 2000 works in less than ten years.

Van Gogh was acquainted with Neo-Impressionist painters such as Georges Seurat during his years in France, whose pointillism (painting in tiny dots and strokes instead of elaborate strokes) and divisionism (placing colors next to one another instead of mixing) techniques strongly influenced how Van Gogh developed his recognizable style.

The artist would sometimes place thick sums of paint directly onto the canvas with his palette knife, forming almost sculptural canvas surfaces. At the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, the exhibition offers visitors magnifiers in order to examine various remnants such as hair, glass shards, and sand embedded in the paint on canvas. The disarray in some of Van Gogh’s paintings accurately represent the mayhem happening in the artist’s inner psyche. Oil painting, to a certain extent, was Van Gogh’s temporary salvation and conduit to the outside world.

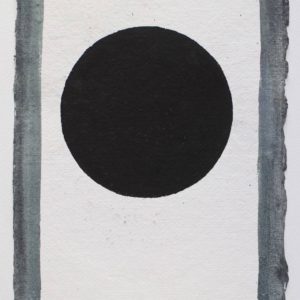

Kazimir Malevich – The Icon

Malevich’s early trainings at Stroganov School of Art in Moscow consisted of training in painting, sculpture and architecture. Between 1907 and 1913, Malevich’s style radically shifted away from primitivism, cubism and futurism, and arrived at his best known phase – Suprematism. Supremacists primarily focused on the demonstration of geometric shapes and colors in their purest forms. Malevich thought to abandon the practice of imitating the material and external world, thus to create a new reality by carefully construction geometric shapes on canvas through mathematics. (Source: Jstor)

Malevich worked with the utmost rigor and skill, constantly strived to present color and shapes in their idealized state; his solution was a completely flat, but thoughtfully textured canvas surface. In some works, Malevich manipulated paint with such control, that the finished surfaced had a voluminous, sculptural quality. In addition, the artist also experimented with gloss and matt surfaces to fully demonstrate the potential of paint and colors.

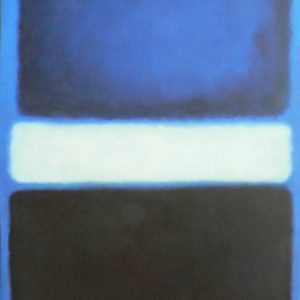

Mark Rothko – The Sectionals

Influenced by sentiments of alienation as an immigrant, the Great Depression and World War II, Rothko began his psychological introspection into the world’s archaic roots and heritage, which resulted in highly expressionistic canvases. By the 1940s, Rothko radically abandoned all figurative and representational subjects from his paintings, and began to use rectangle “sectionals” of colors layered on top of base paint to create the most recognizable color field canvases we know today. Unlike other Abstract Expressionists, Rothko does not communicate emotions through gestural forms, but rather through the properties of color and the rectangle sectionals as universal language to speak to the human collective psychology.

The paintings’ titles are relatively suggestive of their process. “Red on Maroon” is prepared with maroon pigments in rabbit glue, which dried to a matte finish. Rothko applied a second layer of maroon paint, then scraped the layer off to leave a thin veneer of color, thus creating a sense of depth. Finally, the artist applied red paint in swift brush strokes to create the top layer color “sectionals”. Though Rothko’s paintings are remarkably abstract and abstruse, the artist insists on their expressive quality. The rectangular sectionals are considered universal languages to be experienced and understood by all. Many still weep in front of those monumental walls of color, submerged in the most ernest expression of human emotions. (Source: Tate)

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.