One to Watch

Stefan Osnowski’s Modern Woodblock Prints

Stefan Osnowski’s Modern Woodblock Prints

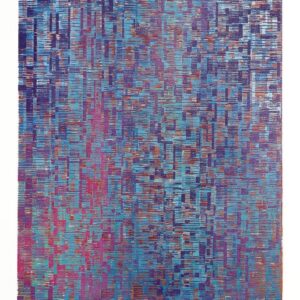

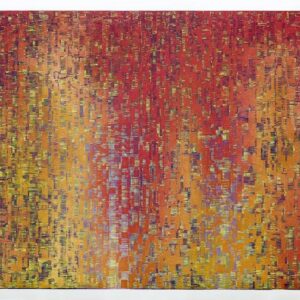

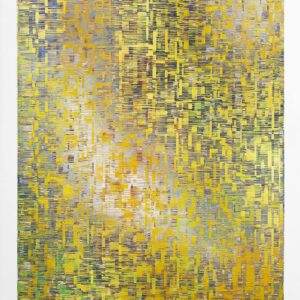

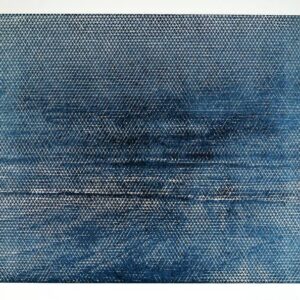

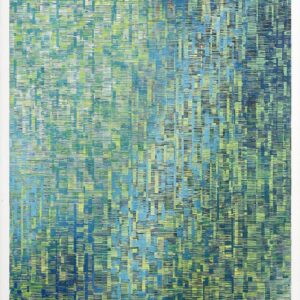

Stefan Osnowski’s woodblock prints meld tradition into modernity. He uses centuries-old techniques to create shimmering images that call to memory both serene landscapes and digitized walls of code.

His work has been featured in exhibitions throughout Europe, even as far as Brazil, and his talent was most recently recognized through the receipt of the 2024 Luxembourg Art Prize (3rd prize). An already illustrious career and a mesmerizing practice steeped in visual culture are what make Stefan Osnowski One to Watch.

Tell us about who you are and what you do. What’s your background?

My name is Stefan Osnowski, and I am a German visual artist based in Lisbon, Portugal. I hold a Master’s degree in Fine Arts from the University of Greifswald in Germany. My work revolves around woodcut printing—one of the oldest reproduction techniques—which I transform into a digital visual language to create hybrid landscapes that merge technology and nature, chaos and order.

I was born in a small town in former East Germany, surrounded by rivers, lakes, and forests. Growing up in this wide landscape, I found freedom in nature—we played in flooded peat pits, built imaginary islands among the reeds, and took boats up the river. This deep connection to nature continues to shape my work today. My images reflect the landscapes of my childhood, infused with a longing for the sea, mountains, and distant places.

What does your work aim to say? What are the major themes you pursue in your work?

My work explores themes of space, perception, and the intersection of technology and nature. I challenge the precise, technological, and often emotionless depiction of digital reality by embracing a quiet, minimalistic aesthetic of reduction and subtraction. My work also blurs the line between rationality and emotion, creating a dynamic interplay of geometric harmony, disharmony, figuration, and abstraction.

A key aspect of my practice is the fusion of woodcut printing with digital media. Transforming an image into an abstract binary code of positive and negative space, meticulously carved by hand, introduces a tension between tradition and technology. In an era dominated by synthetic visual filters and automated perception, I use the same digital strategies in woodcut, yet my final images remain analog—imperfect, tactile, and alive with the traces of craftsmanship.

I often focus on transient or undefined spaces, such as Unorte, a series on man-made, interchangeable places, or Wilderness, which translates landscapes into a digital language, resembling flickering screens. My latest project, Arcadia, explores the concept of idealized, imagined landscapes and computer-generated images, examining how mathematical structures and fragmentation can shape perception. Each woodblock print involves repetitive, instinctive carving, careful inking, hours of manual recurring pressing, and weeks of drying—making the process as meaningful as the final image.

Can you walk us through your process for creating a work from beginning to end?

My process begins with a concept or theme that intrigues me—inspired by landscapes, mathematical structures, or transient spaces. Sometimes I have a clear image in mind; other times, I draw from my own photographs as references. For abstract works, I rely more on instinct and intuition.

I start by preparing the woodblock, first blackening its surface to better control light gradations. Then, I sketch a grid structure in pencil and begin carving the lines, cutting away areas to slowly reveal the image—this forms the luminous traces of the final composition. Printing is a meticulous process. The woodblock is inked with special oil-based colors, requiring careful coordination to maintain contrast. The paper is then placed and pressed manually using glass lenses, a physically demanding process that can take hours. Finally, the print is carefully lifted from the block and left to dry for several weeks before completion.

How does your work comment on current social and political issues?

My work indirectly engages with social and political issues by reflecting on how we perceive and interact with the world in an era dominated by digital imagery. We live in a time of visual overload, where images are filtered, manipulated, and often detached from reality. Through woodcut printing —a slow, physical, and manual process—I challenge the hyper-smooth aesthetics of digital media and question the way technology shapes our perception. By merging traditional techniques with digital influences, my work highlights the tension between the analog and the virtual, between the human hand and machine precision.

Projects like Unorte explore man-made, interchangeable spaces that reflect urbanization and displacement, while Arcadia investigates our longing for idealized, constructed landscapes. In this way, my work is not a direct political statement but rather a reflection on contemporary visual culture, urging viewers to slow down and reconsider the reality behind the images they consume.

How do you hope viewers respond to your works? What do you want them to feel?

I hope my work invites viewers to slow down and engage with the act of seeing in a more conscious way. In a world saturated with fast, digital imagery, I want my prints to offer a counterbalance—demanding time, distance, and reflection. I aim to create a sense of tension between order and chaos, abstraction and figuration, technology and nature. Some works may evoke a feeling of stillness, while others create a flickering, almost unstable visual experience, much like a digital screen.

I want viewers to question their perception; to feel both disoriented and drawn in. Beyond that, I hope my work resonates on a personal level—whether through the textures, the landscapes, or the interplay of light and shadow. If someone finds a moment of recognition, curiosity, or contemplation in my works, then I feel I’ve achieved something meaningful.

If you couldn’t be an artist, what would you do?

As a boy and teenager, I wanted to become a captain. I dreamed of being on a ship, sailing the world’s oceans. Perhaps today, I would be working on a research vessel in Antarctica or as a marine biologist in the coral reefs of Australia. Maybe as an ecologist in the Amazon, striving to protect the land or manage it sustainably in harmony with the rainforest. Ultimately, I would likely be involved in any field directly focused on the protection and preservation of untouched nature.

Who are some of your favorite artists, and why?

Some of my favorite artists include William Turner, Gerhard Richter, Anselm Kiefer, Hans Hartung, Cy Twombly, Richard Serra, as well as Anselm Reyle and the Hungarian Marton Nemes. The list could go on much longer. I particularly admire Anselm Reyle for his innovative approach to abstraction and his playful yet critical exploration of contemporary visual culture, making him a key figure in today’s art scene. His use of materials and vibrant color contrasts creates tension, which I find very inspiring.