Art We Love

First Look: Golden Future by Igor Bleischwitz

First Look: Golden Future by Igor Bleischwitz

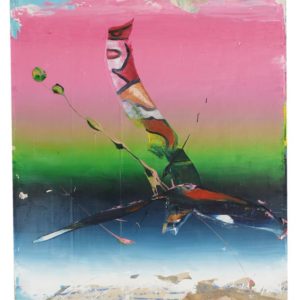

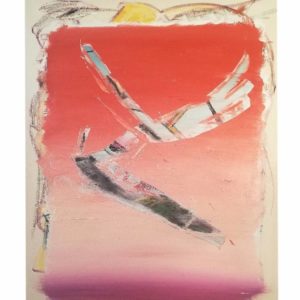

At a glance, Igor Bleischwitz’s paintings are reminiscent of the vivid color fields of Mark Rothko. But rapid paint splatters and jagged cuts interrupt the placid surfaces, revealing glimpses of other images lurking underneath. In each painting, Igor creates, destroys, and finally excavates these pictures beneath the surface, slashing through his final layers of paint to provide just a glimpse of what once ruled the canvas.

The multitude of paint layers that have been built up and scraped away turns these paintings into historical records, registering each moment in time in the process of their creation. Born in 1981 in the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, now part of present day Kazakhstan, the Berlin-based painter is attuned to the cycles of history and its currents of destruction and rebuilding. Born out of the pandemic, Igor’s new series urges us to contemplate our relationship with the past, and the collective name Golden Future suggests we view these works through a lens of hopefulness as well.

Tell us a bit about yourself and your background as an artist.

I had my first experience with art when I was a child. My hometown in the former USSR was visited by the cosmonauts very often. I was fascinated by space flight and all the space missions and started to make some collages and drawings about it. Later nature became a very important inspiration. Maybe that’s a reason why my work is often about the Unknown, a Secret, and Time.

What inspired this particular series?

The Golden Future series was inspired by the, let’s say, current issues on our planet like wars, natural disasters, the Coronavirus pandemic and other manmade crises. Hope is a very thin layer above all this.

Speaking of layers—can you walk us through your process of creating one of these paintings, from beginning to end?

The visual aesthetics of the Golden Future series exploits the tradition of Abstract Expressionism and the art of Mark Rothko in particular. The space of the canvas is filled with horizontal colorful blocks, but in contrast to the American artists, I am breaking the smooth surface by mechanically cutting [into] the paint. The technique includes the following steps: a realistic portrait or still life is created, then it gets painted over several times with solid colors. When the paint dries, the top layers are scraped off, and the original pattern begins to show through. The work is carried out instinctively, therefore the exposed fragments rarely show what was originally created.

As the complexity increases, texture and depth appear, creating the multilayer effect.

How does it feel to paint over your painstaking, realist images?

It feels very painful. A finished realistic painting is done and ready to be shown. At the same time I have this idea in my head that it is not enough. So in this moment I start to analyze which colors are significant to create a color code of this realistic motif. With these colors I paint over the [original] motif and work it out.

What does this process of hiding and rediscovering paint layers mean to you?

The process of creating works is similar to the life cycle of frescos. The drawings on the walls of ancient temples and mansions have been painted over with new images over the centuries in similar ways. Today, these antique images are carefully peeled by restorers seeking the original. On the contrary, I pay attention to all paint layers, comprehending and conceptualizing each of them, as well as the process of the artwork’s creation. Painting, therefore, turns into performance, and each stage forces me to reincarnate. I start off as the author of the image, then I turn into the vandal who paints over the work. Following that, I take on the role of a restorer, who carefully removes the later layers. Finally, like a true archaeologist, I maintain layered fragments and keep the historical stages.

You liken your process to archeology—how does your work explore our instinct for preservation?

The desire for preservation has always been the priority—nothing should be lost and forgotten, and every stage of work should be seen and understood. Oblivion means death, and fear of death is the strongest emotion that has always haunted humanity.

What do you hope audiences take away from these works?

I hope that it gives an opportunity to think about the hidden part, about something in [someone’s] life that was forgotten, hidden; and about time and the importance of the things they do.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections, and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.