Art History 101

The Legacy of Ansel Adams

“A good photograph is knowing where to stand.” – Ansel Adams

In celebration of American landscape photographer Ansel Adams, we take a look back on the artist’s accomplishments and the impact he made in both the realms of art and nature.

Adams showed an interest in the natural environment from an early age, collecting insects and exploring local sites like Lobos Creek, Baker Beach, and Lands End in his hometown of San Francisco, California. He received his first camera, a Kodak Brownie, from his father during a family trip to Yosemite National Park in 1916. This trip proved momentous for the young Adams. Of his first glimpse of Yosemite Valley, he wrote, “The splendor of Yosemite burst upon us and it was glorious…One wonder after another descended upon us….A new era began for me.”

This experience prompted him to make subsequent trips with a more advanced camera, a tripod, and a more refined skill-set. Adams learned darkroom techniques, read up on photography magazines, and improved his stamina by hiking with the Sierra Club, allowing him to reach higher elevations and cross difficult terrain to capture the perfect shot.

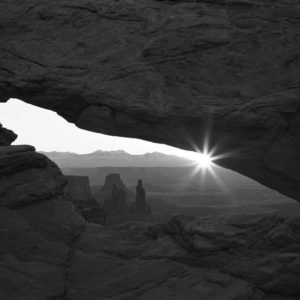

His sublime, black and white landscapes are characterized by their precision, eschewing effects like soft focus and etching in favor of sharp focus and high contrast. Adams’ photography career took off following the publication of his first portfolio, Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras, which included his iconic Monolith, The Face of Half Dome. After gaining commercial attention, he began experimenting with larger subjects and close-up shots.

A steadfast advocate for conservation, Adams utilized his images to document the beauty and promote the significance of Yosemite and other nature reserves, like Glacier National Park in Montana and Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming. He produced Sierra Nevada: The John Muir Trail, a limited edition book of stunning landscape photographs, which later proved instrumental in the Sierra Club’s movement to designate King’s Canyon as a national park. Though environmentalism as a movement was still in it’s nascent stage, Adams’ ability to articulate the “wilderness idea” through his photography was instrumental in growing public and political support for national parks.

“We all know the tragedy of the dustbowls, the cruel unforgivable erosions of the soil, the depletion of fish or game, and the shrinking of the noble forests. And we know that such catastrophes shrivel the spirit of the people… The wilderness is pushed back, man is everywhere. Solitude, so vital to the individual man, is almost nowhere.” – Ansel Adams

Adams’ striking photographs also attracted the eye of the traditional fine art world in the 1960s and 1970s, spurring him to reprint carefully selected negatives from his archive. Philadelphia’s Kenmore Gallery exhibited his images, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art held a major retrospective exhibition in 1974. It can be argued that in addition to his contributions to conservation, Adams legacy also includes elevating the medium of photography. Before his time, photography had been widely regarded as a ‘lesser art form’ to painting, drawing and music. He instructed his students, “It is easy to take a photograph, but it is harder to make a masterpiece in photography than in any other art medium.”

Adams breathtaking landscape photographs live on today as some of the best examples of the medium to date. His images are revered for capturing an idyllic natural world of the past, and in several cases, preventing those mystical, pristine sceneries from being lost forever.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.