Art History 101

Peter Paul Rubens and the Female Form

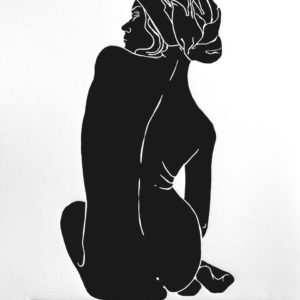

Peter Paul Rubens is synonymous with Baroque style. During his life he produced paintings and altarpieces in brushstrokes dramatic and sensuous, emphasizing movement and suggesting a new naturalism. Rubens is noted for his pioneering new style of painting figures, full figured and even more nuanced. Though painted in and for the eye of the male, Rubens’ iconic treatment of the female figure in particular sparked new definitions of form.

In the late sixteenth century, Rubens undertook an apprenticeship in Antwerp where he studied under Mannerist artists and found inspiration in the work of the Old Masters. After 1600 he travelled throughout Europe, seeing and studying the work of Titian and Tintoretto in Venice, Caravaggio in Rome, and later Raphael in Spain. Informed by their Renaissance classicism, Rubens imbued a heightened sense of realism in his own style, expressed through human form. His subjects retain a softness in fleshy detail, delicately arranged and woven throughout an entire canvas.

Rubens treatment of the curvaceous female body was remarkable, marked as a distinct woman central to his legacy. A reflection of the time and in line with the popular Baroque tradition, Rubens’ woman was plump in size and sexual appeal, giving rise to the term “Rubenesque.” The Three Graces depicts three virgins of classical antiquity in rich color and fullness of figure, establishing a connection between them and the surrounding fertile and lush natural world. The leftmost figure is thought to be painted after Rubens’ wife, Hélène Forment.

Though Rubens treatment of the female form retained the male perspective and projection that was standard in art until the twentieth century, he’s lauded for imbibing some sense of the innate qualities and experiences of womanhood. When the artist was charged with producing a series of paintings that represented the life of Maria de Medici, he relied on allegorical scenes to depict politically charged moments with subtlety and maintained Marie’s eminence through allegory. Rubens spared no dramatic nuance in celebrating Marie’s life and political accomplishments, treating female archetypes of motherhood and marriage with a sense of importance that was unusual for the time.

Love reading about all things art? You can have articles from Canvas, curated collections and stories about emerging artists delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Saatchi Art Newsletter.